Upon returning to Philadelphia, Tokio Ueyama continued his studies at PAFA and finished in 1921. After his return to Los Angeles in 1922, aged thirty-two, he quickly became involved with an art community in Little Tokyo, the area of downtown Los Angeles around East First Street populated by people of Japanese descent.1 Over the next two decades, Ueyama exhibited regularly up and down the West Coast and, from January 1927 to August 1941, worked at the Bunrindo bookstore located at 303 East First Street.

Soon after his return to Los Angeles, Ueyama cofounded—along with artists Hojin Miyoshi (1888–unknown) and Sekishun Masuzo Uyeno (c. 1892–unknown) and poet T. B. Okamura (dates unknown)—the art association Shaku-do-sha. Dedicated to “the study and furtherance of all forms of modern art,” the Shaku-do-sha organized exhibitions in Little Tokyo.2 Some of these featured work by Japanese artists—such as the first group exhibition held in 1923 at the Japanese Union Church, to which Ueyama contributed four paintings—as well as non-Japanese artists, including the photographer Edward Weston.3 By 1927, the author Ione Rayburn described the Shaku-do-sha as a “vital and flourishing colony.”4

In 1922, Ueyama exhibited three paintings at the second exhibition of the East West Art Society at the San Francisco Museum of Art at the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco.5 He also participated in regular exhibitions in California, including the annual series Painters and Sculptors of Southern California, organized by the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art (now the Los Angeles County Museum of Art). Later, he would contribute to the annual series of Southern California art hosted by the Fine Arts Gallery of San Diego (now the San Diego Museum of Art).

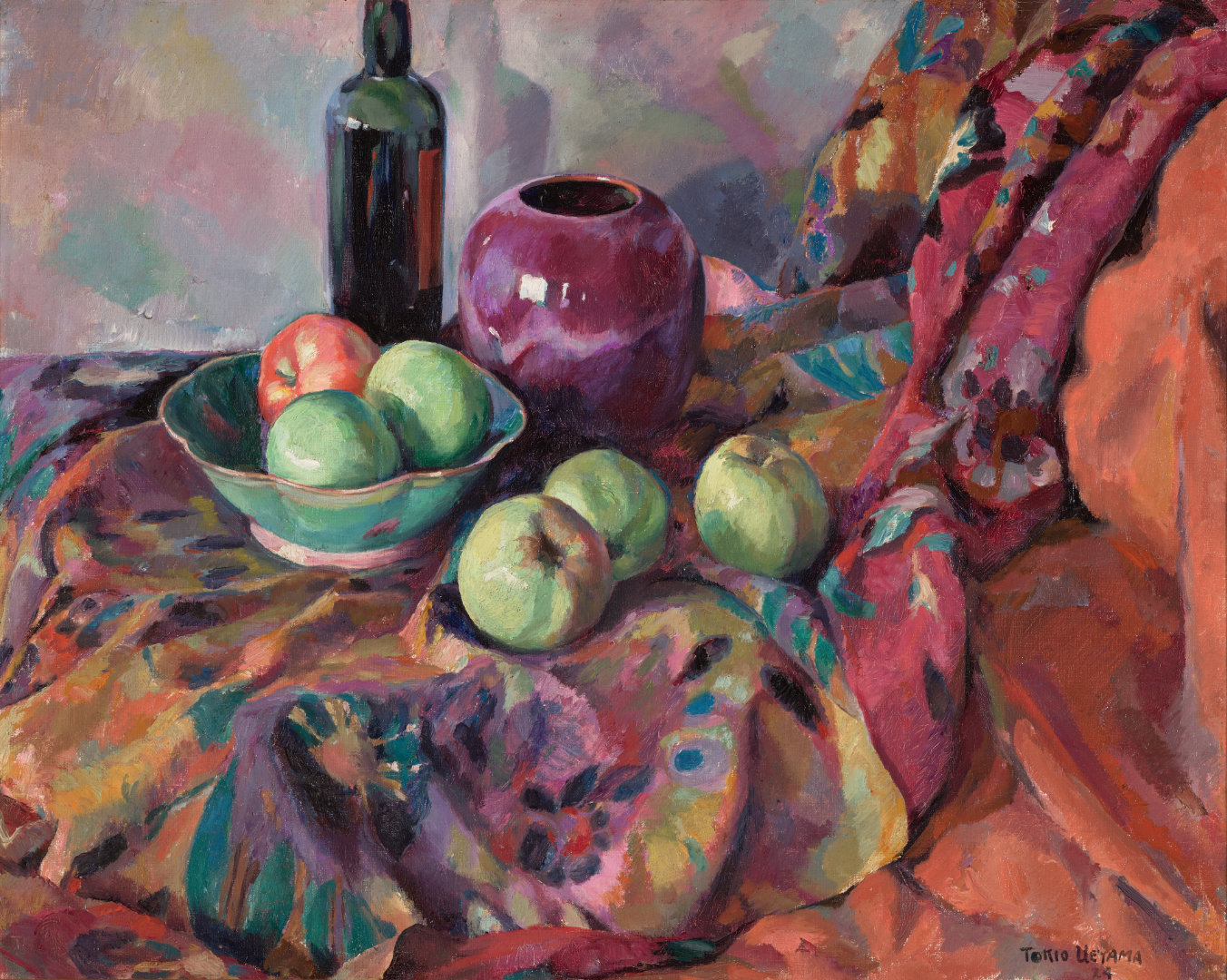

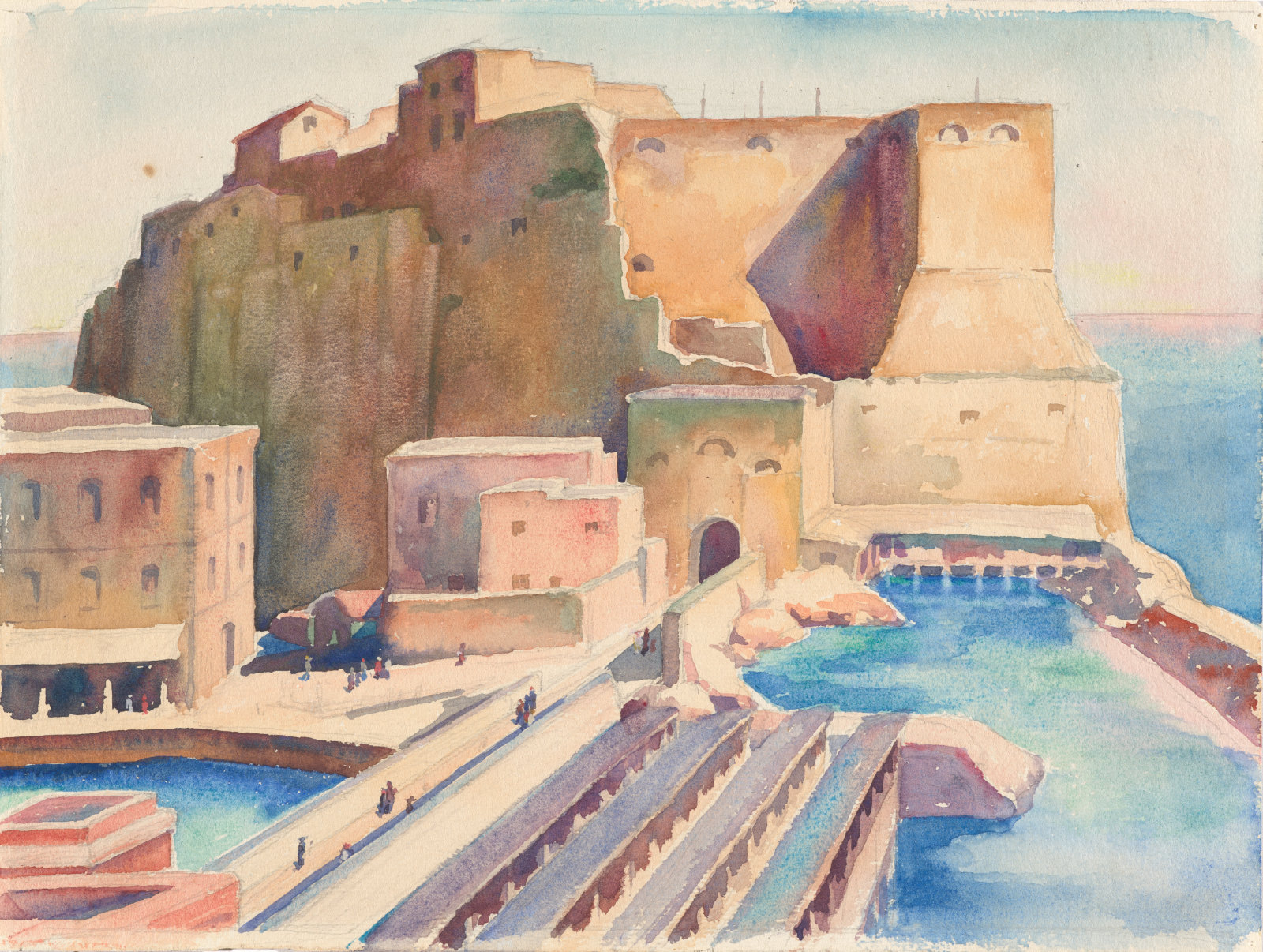

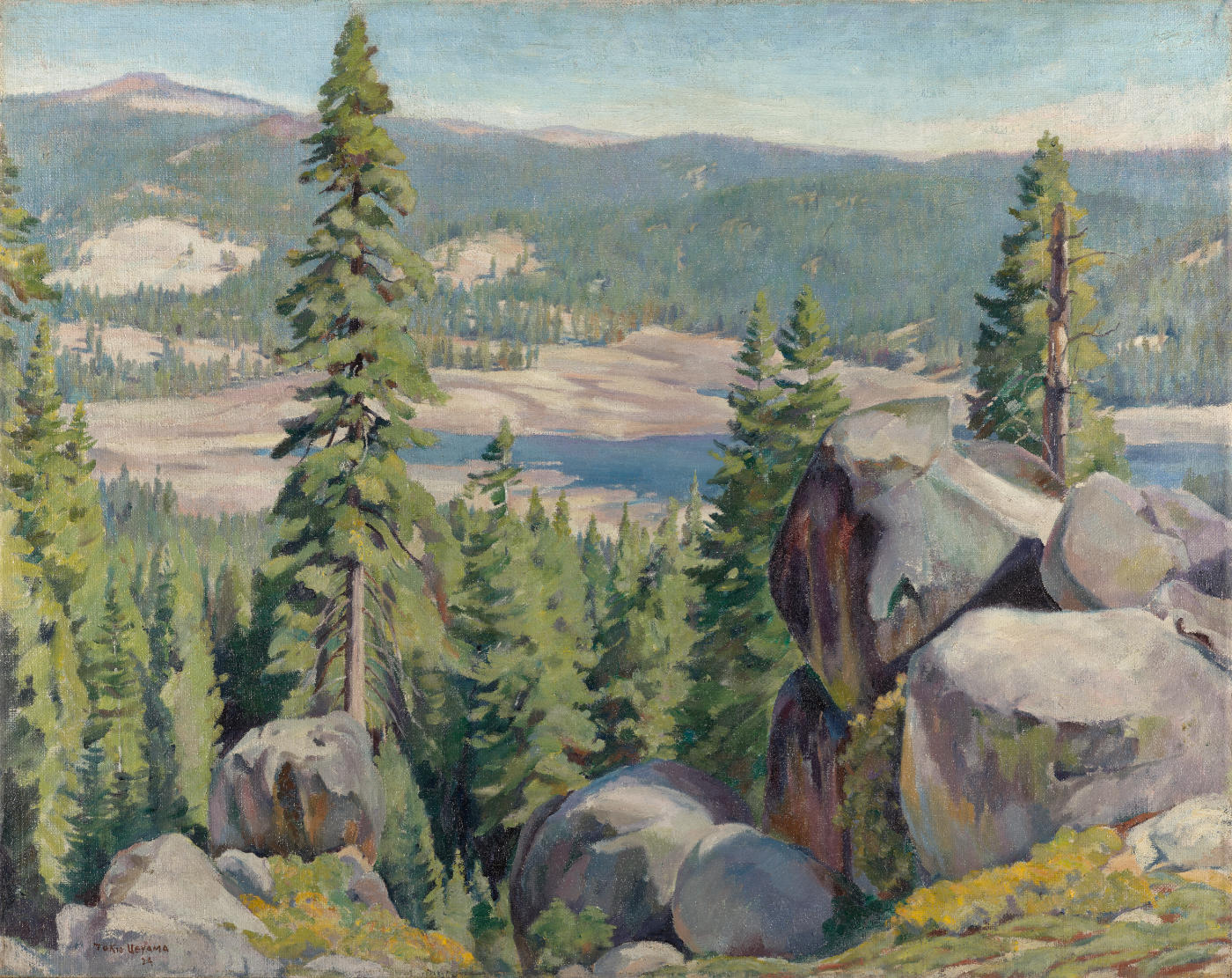

In September 1924, Ueyama mounted his first known solo

exhibition of twenty-five artworks at the Sumida Music Store,

a venue used by the Shaku-do-sha, located at 325 East First

Street. He included his 1924

Self-Portrait

(no. 25 in the 1924 catalog) as well as the 1920 watercolor

Self-Portrait

(no. 25 in the 1924 catalog) as well as the 1920 watercolor

The Castle in Naples

(no. 13). While difficult to determine without visual

evidence, it is likely that he also included his 1924

Still Life (cat. 5, illustrated on this page, no. 10

or no. 19) and a currently untitled 1924 landscape of an

alpine California landscape (possibly

The Castle in Naples

(no. 13). While difficult to determine without visual

evidence, it is likely that he also included his 1924

Still Life (cat. 5, illustrated on this page, no. 10

or no. 19) and a currently untitled 1924 landscape of an

alpine California landscape (possibly

In the High Sierras, no. 23). This selection of work provides a snapshot of the

subjects to which Ueyama would remain faithful for the rest of

his career: the human body, portraiture, still life, and

landscape.

In the High Sierras, no. 23). This selection of work provides a snapshot of the

subjects to which Ueyama would remain faithful for the rest of

his career: the human body, portraiture, still life, and

landscape.

In November 1924, Ueyama sent an exhibition of twenty-five works to the gallery at the University of Oregon in Eugene, where his friend and PAFA classmate Nowland B. Zane (1885–1945), a professor there, had probably invited him to exhibit.6 During this exhibition, reviewers attempted to reconcile what one called Ueyama’s “double heritage of oriental blood and occidental training.”7 Another pointed to the “decorative” nature of Japanese influences and the “realistic” influences of Western academies.8 Margaret Skavlan interpreted Ueyama as “an art hybrid, laboring between his Japanese decorative sense and a training, here and abroad, toward realism.”9 Gordon Chang has pointed out that art by people of Asian descent in the US “was constantly subjected to the trope of being a bridge between ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’ art.”10 Oregon reviewers seem to have pushed particularly hard to build this bridge, especially given that Ueyama’s paintings do not conform to what Wang has identified as “stereotypical notions of ‘Asian imagery,’ such as landscape or nature paintings done with brush and ink.”11

In contrast, Los Angeles critics were more likely to point to the thorough westernization of Ueyama’s practice. Los Angeles–based art critic Antony Anderson called Ueyama’s painting The Fur Coat (unlocated) “a portrait of much distinction in handling, not in the least Oriental in feeling or treatment.”12 Similarly, an unknown reviewer remarked of Portrait of Miss B (unlocated) that “Ueyama is a thoroughly Americanized Japanese. His composition has the occidental balance, his whole technical method is absolutely American.”13 These reviews from Oregon and Los Angeles signal that Ueyama’s work challenged ingrained expectations about Japanese, American, and Japanese American art. As Chang has written, Asian American identities are fluid, multiple, shifting, and unstable.14 Acknowledging this reality helps blur the unproductive East/West lens through which Ueyama’s work was viewed during the 1920s and 1930s.

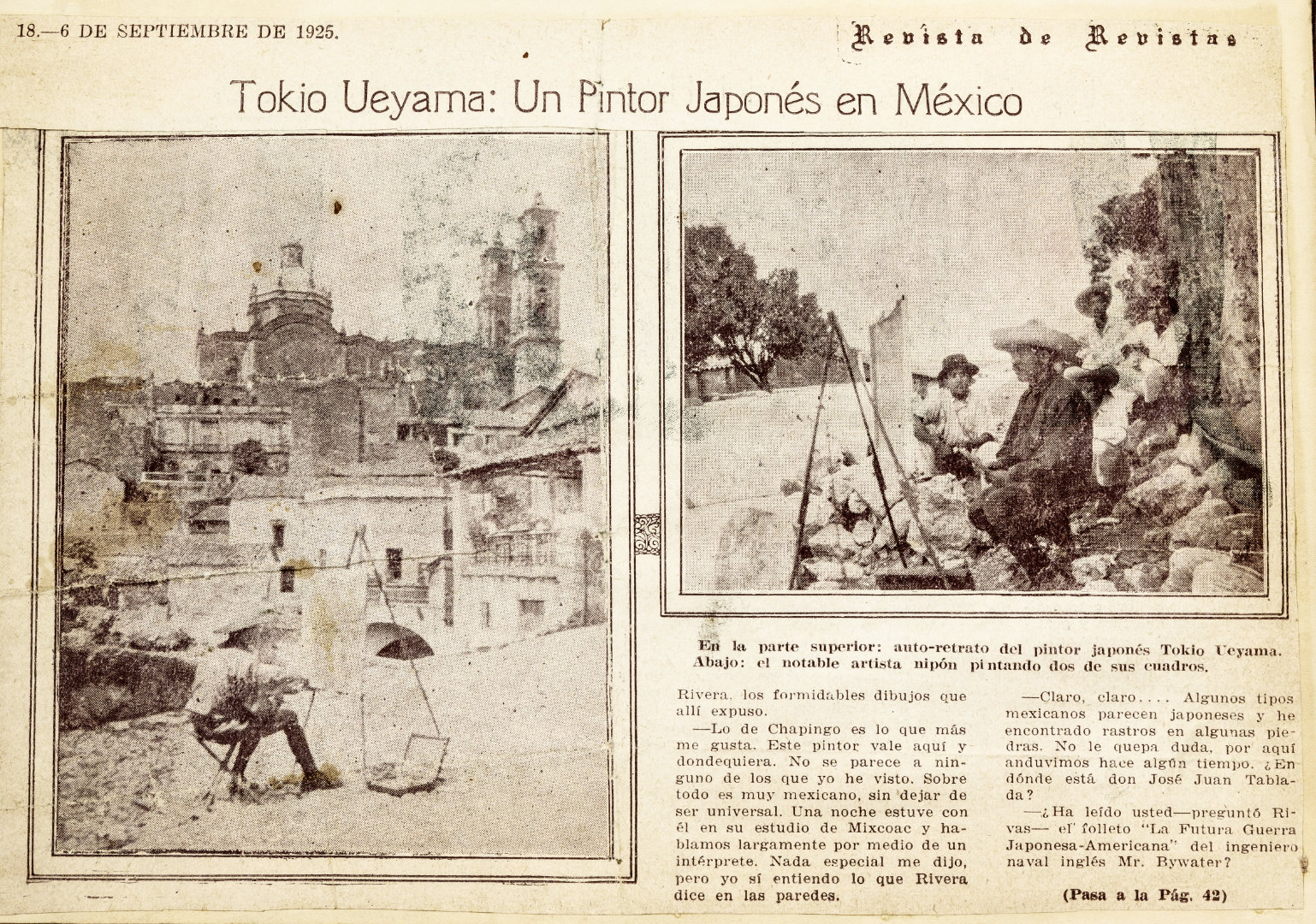

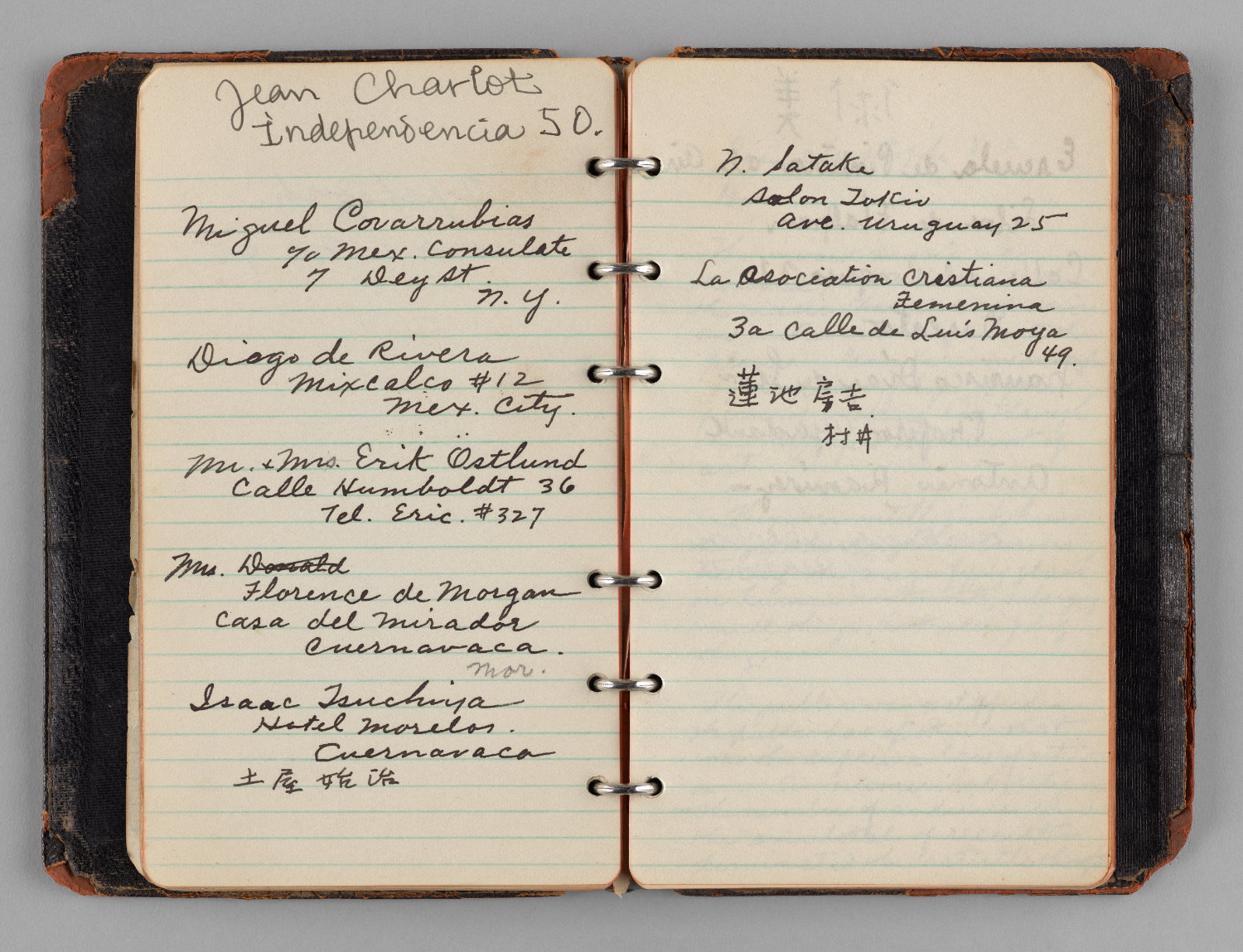

In 1925, Ueyama made a second major international trip, this

time to Mexico for the summer. In Mexico City, he listened to

a lecture by Diego Rivera (1886–1957) at the Association of

Christian Women and spent time with the muralist, even keeping

up a correspondence after his return to the US.15

In an interview for Revista de Revistas, Ueyama says

he spent time with Rivera in his studio and admired his work,

especially the mural in the Chapingo chapel.16

In Mexico, Ueyama probably met Edward Weston (which may have

created the connection for Weston’s Shaku-do-sha exhibitions)

and Jean Charlot, who wrote his address in

Ueyama’s notebook.17

Ueyama traveled to

Ueyama’s notebook.17

Ueyama traveled to

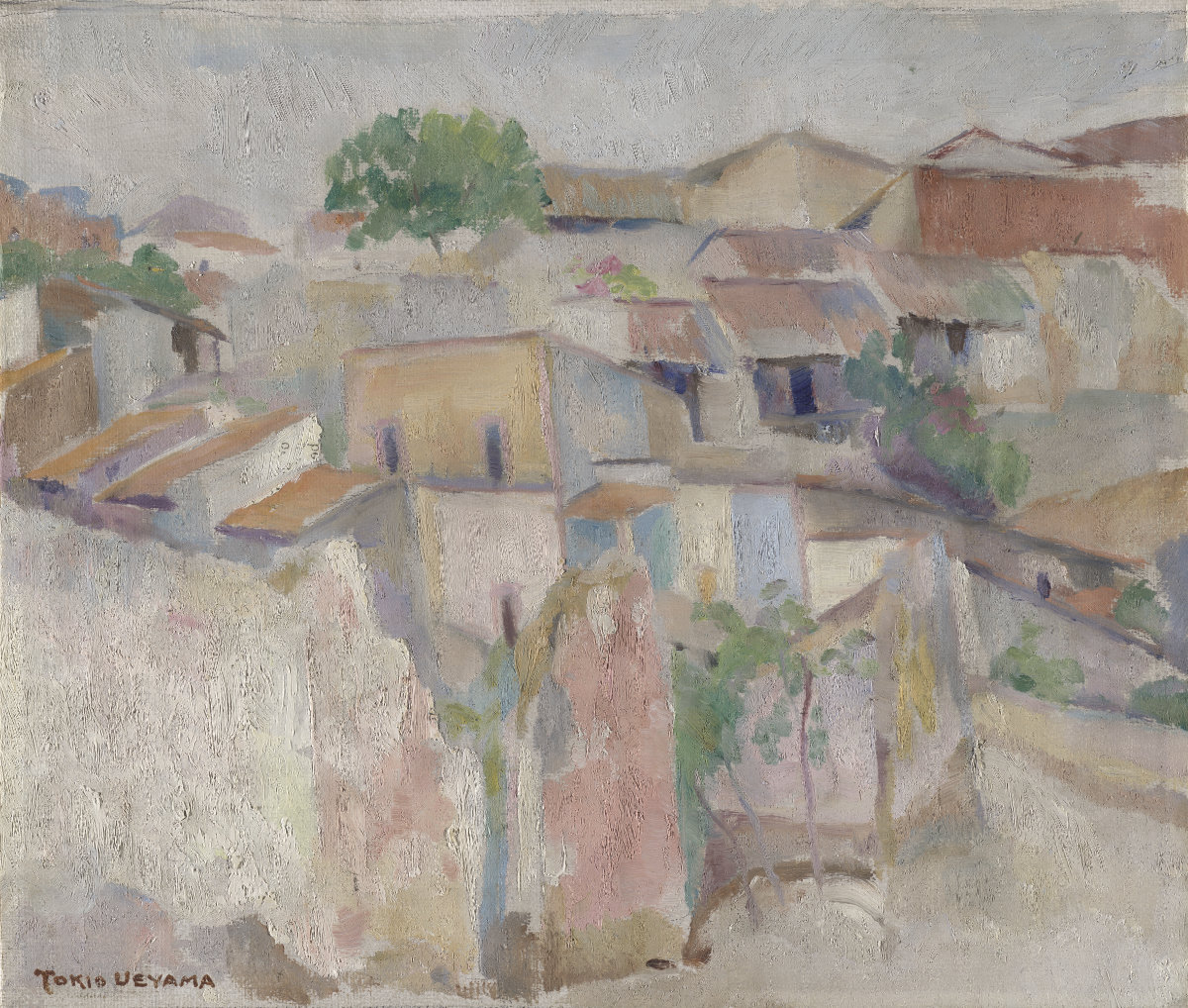

Cuernavaca

and Taxco, where he painted the Church of Santa Prisca from

multiple perspectives (cat. 8 and fig. 1).

Cuernavaca

and Taxco, where he painted the Church of Santa Prisca from

multiple perspectives (cat. 8 and fig. 1).

During the later 1920s and into the ’30s, Ueyama continued a robust exhibition schedule in Little Tokyo and Southern California. In the spring of 1928, he exhibited Portrait in Black, featuring a fashionable Japanese woman in a black fur coat and cloche hat (cat. 10, illustrated below). The sitter, Suyeko “Suye” (pronounced soo-eh) Tsukada (1897–1969), would become his wife on July 23, 1928, in a ceremony at California’s Mission Inn in Riverside.

Like many of Ueyama’s portraits, Portrait in Black received favorable reviews in the Los Angeles press. Antony Anderson commented on the “imposing and exceedingly skillful portrait of a young Japanese woman.” The artist is, he wrote, “one of our finest portrait painters, indeed, quite among the good portraitists of the country.”18 Ueyama’s landscapes, too, were praised. When his Monterey was on display in 1929, the artist and critic Arthur Millier described it as “flooded with clear light which creates a fine pattern of light and shadow on headlands, houses, and blue water” (cat. 11, illustrated below).19

In February 1936, Ueyama held a significant solo exhibition of

sixty-one works at the Miyako Hotel in Little Tokyo. Spanning

more than a decade of output, the artworks included studies,

watercolors, and finished oils representing diverse locations

in Mexico, California, and Oregon. His repertoire remained the

same: still life; figure paintings, including

The Nude

(no. 6, illustrated on the cover of the 1936 catalog);

portraits, including that of Suye (cat. 11, illustrated on

this page, no. 14 in the 1936 catalog) and his own

The Nude

(no. 6, illustrated on the cover of the 1936 catalog);

portraits, including that of Suye (cat. 11, illustrated on

this page, no. 14 in the 1936 catalog) and his own

self-portrait

(no. 21); landscapes, including a striking representation of

California’s

self-portrait

(no. 21); landscapes, including a striking representation of

California’s

Red Rock Canyon

(no. 40); and Mexican subjects, including

Red Rock Canyon

(no. 40); and Mexican subjects, including

At Cuernavaca

(no. 60) and the church in Taxco (no. 9). In an undated

clipping, an unknown author calls Ueyama’s Miyako Hotel

exhibition “one of the best exhibits ever held by a Japanese

artist.”20

Another clipping details the artist’s “wide versatility not

only in technique but in the skill Ueyama uses in handling

landscapes, marines, still life compositions, figure

arrangements, and portraits with equal dexterity and colorful

success.”21

At Cuernavaca

(no. 60) and the church in Taxco (no. 9). In an undated

clipping, an unknown author calls Ueyama’s Miyako Hotel

exhibition “one of the best exhibits ever held by a Japanese

artist.”20

Another clipping details the artist’s “wide versatility not

only in technique but in the skill Ueyama uses in handling

landscapes, marines, still life compositions, figure

arrangements, and portraits with equal dexterity and colorful

success.”21

The same author also trumpets Ueyama’s success in selling

twenty-seven of sixty-one paintings and nods toward his

upcoming trip to Japan as an art ambassador for the Los

Angeles Art Association, which had appointed him its envoy to

develop relationships that might result in exhibitions of

Japanese artwork in California and of California artwork in

Japan.22

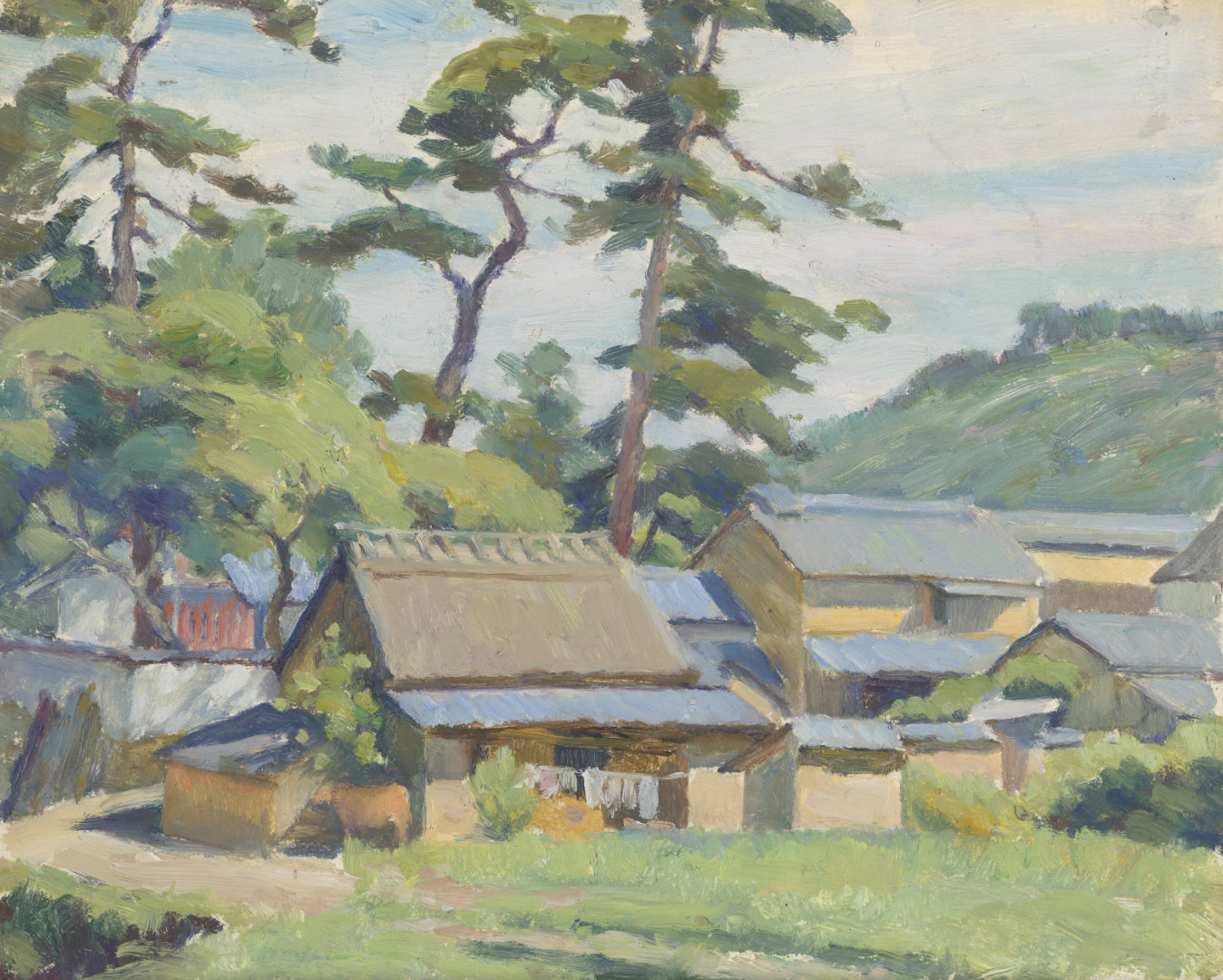

Ueyama departed for Japan in May 1936. Over the next thirteen

months, he traveled around the Kanto, Kinki, Kansai, Shikoku,

and Kyushu regions and mounted a solo exhibition at his alma

mater, Toyajyo Elementary School, in July.23

He painted vibrant scenes, including

Untitled (Japanese Village)

and Untitled (Tori Gate) (cat. 15, illustrated

above).

Untitled (Japanese Village)

and Untitled (Tori Gate) (cat. 15, illustrated

above).

Given Ueyama’s positive reviews, regular exhibitions, and significant trip to Japan, the 1930s seem to have been a successful decade, but his diary from this period shows ups and downs. The deaths of his father in December 1939 and of Suye’s father the following month were heavy blows to the entire family, while his inclusion in the 1940 Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco was a professional coup. Friends including Zane, artist Paul Landacre (1893–1963), Mr. and Mrs. Wilson, and family members show up regularly, though health concerns sometimes keep his body and mood low. In retrospect, his diary—punctuated by notes on German expansion, European alliances, and the deteriorating relationship between Japan and the US—seems both prescient and ominous.24

-

For an overview of Little Tokyo’s history, see “Little Tokyo Historic District,” National Park Service, accessed November 15, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/places/little-tokyo-historic-district.htm. ↩︎

-

See “Photographs by Edward Weston on Exhibition,” undated but probably July 1927, red scrapbook, 17, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. Karin Higa provides the date of July 7, 1927, in her A View from Within: Japanese American Art from the Internment Camps, 1942–1945 (Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 1992), 30. For the most complete account of the Shaku-do-sha, see Higa, “Hidden in Plain Sight: Little Tokyo between the Wars,” Asian American Art: A History, 1850–1970, edited by Gordon Chang (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008). ↩︎

-

The Shaku-do-sha exhibited Weston’s work in 1925, 1927, and 1931. ↩︎

-

Ione Rayburn, “Japanese Artists in California” in “Sports and Vanities,” September 1927, red scrapbook, 37–39, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

On the East West Art Society, see ShiPu Wang, Chiura Obata: An American Modern (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2018) 12. ↩︎

-

Given the date, the number of works included, and period reviews, it is likely that he sent the same (or similar) group as had been exhibited at the Sumida Music Store. See “Japanese Art to be Shown in University Gallery Soon,” Oregon Daily Emerald, October 29, 1924, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1924-10-29/ed-1/seq-1/#words=Tokio+Ueyama; Margaret Skavlan, “Japanese Paintings Are Hung in University Art Gallery,” Oregon Daily Emerald, November 13, 1924, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1924-11-13/ed-1/seq-1/; “Arts Club Will Open Exhibition with Tea,” Oregon Daily Emerald, November 18, 1924, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1924-11-18/ed-1/seq-3/#words=Tokio+Ueyama; “Exhibition of Japanese Artist’s Paintings Will Be Opened Today,” Oregon Daily Emerald, November 19, 1924, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1924-11-19/ed-1/seq-1/#words=Tokio+Ueyama; “Japanese Print Collector Visits Campus Today. S. Doi Paintings to be Presented With Ueyama Exhibition,” Oregon Daily Emerald, November 20, 1924, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1924-11-20/ed-1/seq-3/#words=Tokio+Ueyama; “Work of Japanese Artist Portrays Variety of Style,” Oregon Daily Emerald, December 2, 1924, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1924-12-02/ed-1/seq-1/#words=Tokio+Ueyama; and undated clipping, “Exhibit of Ueyama, Japanese Painter, Opens Wednesday,” red scrapbook, 8 Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

“Work of Japanese Artist Portrays Variety of Style.” ↩︎

-

“Exhibition of Japanese Artist’s Paintings Will Be Opened Today.” ↩︎

-

Skavlan, “Japanese Paintings Are Hung in University Art Gallery.” ↩︎

-

This evaluation, he continues, “assumed that the mainstream of American art was, as America itself, entirely Europe-derived.” Gordan Chang, “Emerging from the Shadows,” in Asian American Art: A History, 1850–1970 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008), x. ↩︎

-

ShiPu Wang, The Other American Moderns: Matsura, Ishigaki, Noda, Hayakawa (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2017), 1. ↩︎

-

Antony Anderson, Art News 21, no. 36 (1923): 8. ↩︎

-

Untitled and undated clipping, red scrapbook, 10, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

Chang, “Emerging from the Shadows,” xi. ↩︎

-

See letters in the Tokio Ueyama papers, which are written by the author Frances Toor. “Correspondence—Toor, Frances, 1926–27,” Tokio Ueyama papers, 1908–circa 1954, bulk 1914–1945, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-6. ↩︎

-

“Tokio Ueyama: Un Pintor Japonés en México,” Revista de Revistas, September 6, 1925, 17–18 and 42. Page 42 is missing in the clipping available in the red scrapbook, 20–21, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. I am grateful to Memphis Despain for translating this article while ShiPu Wang’s research assistant in August 2022. See also a print of Rivera’s Chapingo mural (Partition of the Land) signed by the artist in “Partition of the Land Mural Signed by Diego Rivera,” Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/oversize-3. ↩︎

-

On Weston and the Shaku-do-sha, see Karin Higa, The View from Within: Japanese American Art from the Internment Camps, 1942–1945 (Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 1992), 31. ↩︎

-

Antony Anderson, “Art News From Laguna,” Los Angeles Times, December 21, 1930. Additionally, Los Angeles Times art critic Arthur Millier pointed out the poise of the figure and the painting’s “feeling for textures and character.” Millier called Ueyama “an accomplished and painstaking artist.” Millier, “City’s Japanese Show Art,” Los Angeles Times, December 29, 1929. ↩︎

-

Millier, “City’s Japanese Show Art.” ↩︎

-

“Art Exhibit Draws Many Purchasers,” red scrapbook, 24, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

“Tokio Ueyama’s Success,” March 21, 1936, red scrapbook, 22, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

In a letter sent to Ueyama, the Association stated, “As an artist well trained in the best American schools, and a resident of Los Angeles, we believe that you are in a position to accomplish splendid results in creating a better understanding of the art developments around the Pacific Ocean.” “Correspondence—Miscellaneous, 1916–1936,” Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-4. ↩︎

-

See Memorial Exhibition catalog, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. I am grateful to Noriko Okada for her translation of the Japanese. ↩︎

-

“Diary Excerpts Translated into English, 2023,” Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-9. I am grateful to Noriko Okada for sharing relevant excerpts of her translations. ↩︎