Two self-portraits bracket this exhibition. The Japanese-born artist Tokio Ueyama (pronounced oo-eh-yama; 1889–1954) painted the first in 1924 around age thirty-five. In it, he wears a collarless white button-up shirt open at the neck, the informality of which echoes his loosely brushed-back black hair. A nude female sculpture hovers behind his right shoulder, a testament to the figure of the human body that inspired him. A few years earlier, Ueyama had completed his academic training at the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) and completed a tour of Spain, France, and Italy. He finished this painting before his trip to Mexico during the summer of 1925, where he met artists, including Diego Rivera, Jean Charlot, and probably Edward Weston. For years, Ueyama participated in exhibitions up and down the West Coast and helped organize art groups based in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles, where he made his home. In retrospect, it is easy to read this self-portrait as one of a skilled artist looking curiously and confidently at a world of opportunity.

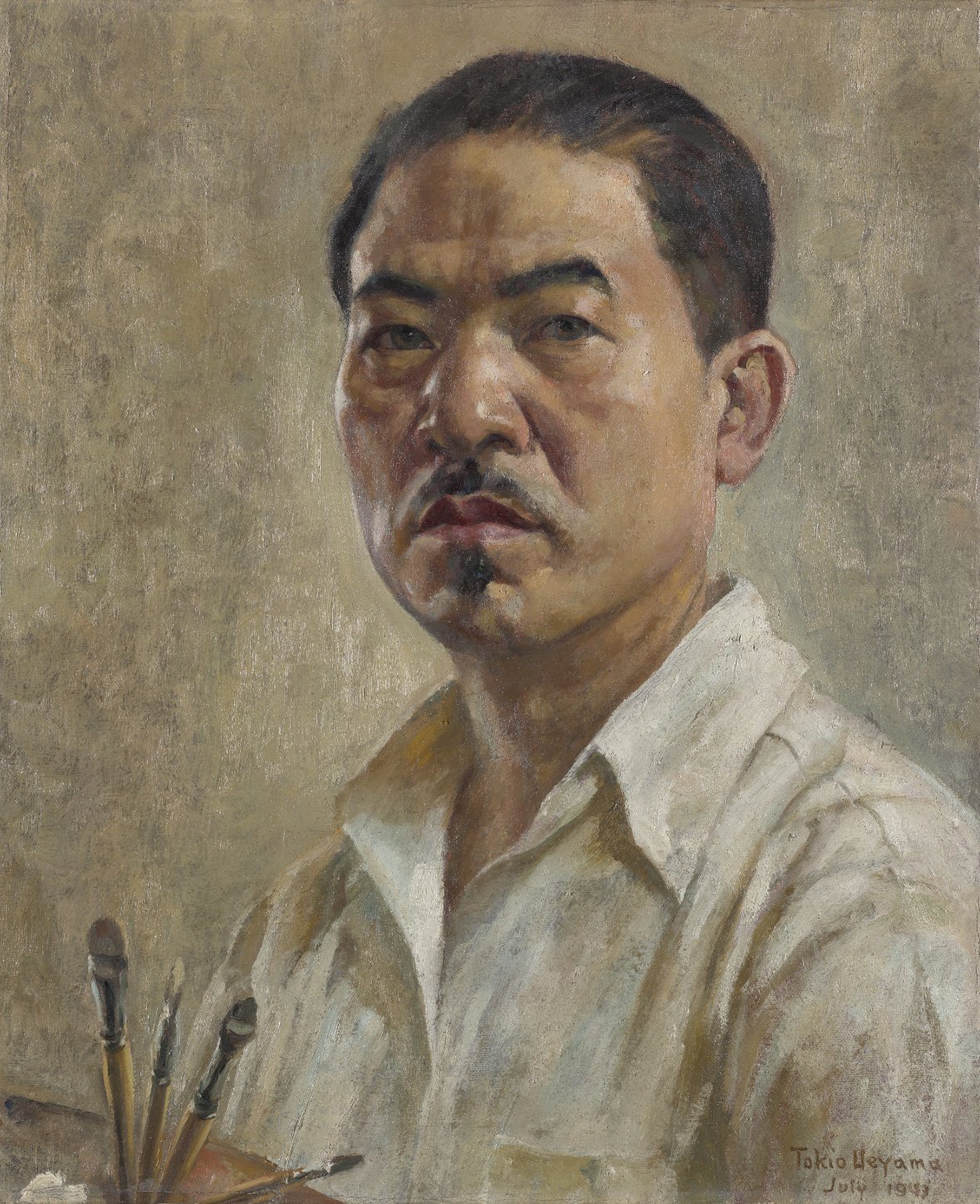

In the second self-portrait, created in July 1943, when he was fifty-three years old, Ueyama maintains a confident pose and outward gaze, though the paint handling has matured and the mood darkened. He is still dressed in a white button-up open at the neck, his thinning hair now carefully groomed. Tighter handling of paint signals careful mastery of the brush learned over years of practice as well as, possibly, the controlled environment in which this was painted: the Granada Relocation Center, best known as Amache (pronounced ah-mah-chee), in southeast Colorado. In this somber yet striking portrait, in which four brushes and a palette reinforce his occupation and align him with centuries of artists’ self-representations, Ueyama proclaims his profession and his personhood—no small thing given the dehumanizing experience of being forcibly relocated as an “enemy alien” during World War II.

The Life and Art of Tokio Ueyama tells the story of this cosmopolitan artist. From age eighteen in 1908 to his death at sixty-four in 1954, Ueyama called the United States his home, even though, as an Asian-born person, he was not allowed American citizenship. As a person of Japanese descent living on the West Coast during World War II, Ueyama and his wife, Suye, along with over 120,000 others, were incarcerated within “relocation centers” hastily built in some of the most remote parts of the American interior.1 For two years, eight months, and twenty-three days, Tokio and Suye lived at the Granada Relocation Center. This exhibition spans the entirety of Ueyama’s life, including his prestigious art training, cosmopolitan travels, life in California, incarceration at Amache, and his and Suye’s creation of the store Bunkado in the heart of Little Tokyo in downtown Los Angeles.

This project is due to the generosity of Ueyama’s friends and family. Many Japanese Americans never recovered the belongings forcibly left behind during World War II, but the Ueyamas were more fortunate. Mr. and Mrs. Wilson—their friends, neighbors, and landlords—protected their belongings and maintained their home during their incarceration. After Tokio’s and Suye’s deaths, their extended family protected and maintained their archives and Tokio’s artwork.

This project is also indebted to the work of pioneering scholar and curator Karin Higa (1966–2013), who rediscovered Ueyama and, thanks to the generosity of the artist’s family, aided the placement of his artworks at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles and helped rehabilitate his life and art through publications. Higa’s work charting Asian American artists across the twentieth century has shaped Asian American art studies, and this essay relies heavily on her foundational scholarship.2

I am also deeply grateful to ShiPu Wang, whose essay in this volume puts Ueyama’s wartime work into conversation with that of other incarcerated people of Japanese descent. Wang’s scholarship stands as a model for rehabilitating overlooked artists’ work and lives through careful archival research and relationships with artists’ families.3 In the introduction to his book The Other American Moderns, Wang highlights the “substantial volume of creative output, superb quality of pictures, and high levels of engagement with artistic, cultural, and sociopolitical discourses” of modern Asian American artists. They are, he writes, “as fascinating as many canonical artists,” and yet remain largely unknown.4 Similarly, the art and life of Tokio Ueyama reveals rich artistic and interpersonal networks, ambitious creative output, and serious, prolonged attention to aesthetics—both his own and those of the art worlds in which he worked.

This essay, in conjunction with the timeline included in this publication, establishes some of the facts of Ueyama’s life. Artworks in the exhibition help illustrate the trajectory of his experiences and aesthetic development. This essay defers to English-language sources, though significant archives in Japanese exist and merit examination. This digital publication establishes a foundation that, I hope, will be useful to those pursuing the many unresolved questions and rich avenues of inquiry presented by Ueyama’s life and work.

-

During World War II, “relocation centers” referred to the ten permanent camps administered by the War Relocation Authority (WRA). “Relocation” and “evacuation” are euphemisms for what were concentration camps, where people were imprisoned not because of any crimes they committed but because of who they were. “Internment camps” and “incarceration camps” have also been used to refer to these locations and are used in this essay. ShiPu Wang, ed., Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo (Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 2023), 7. ↩︎

-

In 1992, Higa curated The View from Within: Japanese American Art from the Internment Camps, 1942–1945 (Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 1992). In 1995, she contributed the essay “Some Notes on an Asian American Art History” to the catalog accompanying the exhibition With New Eyes: Toward an Asian American Art History in the West (San Francisco: San Francisco State University). In 2008, Stanford University Press released Asian American Art: A History, 1850–1970, edited by Gordon Chang, to which Higa contributed “Hidden in Plain Sight: Little Tokyo between the Wars,” an essay in which Ueyama plays a significant role. To date, Asian American Art is the most comprehensive survey of the field of Asian American art and includes hundreds of artists’ biographies. For a beautifully edited compilation of Higa’s writing, see Julie Ault, ed., Hidden in Plain Sight: Selected Writings of Karin Higa (Brooklyn, NY: Dancing Foxes Press in association with the Magnum Foundation Counter Histories initiative, 2022). ↩︎

-

See Wang’s publications Becoming American? The Art and Identity Crisis of Yasuo Kuniyoshi (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2011); The Other American Moderns: Matsura, Ishigaki, Noda, Hayakawa (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2017); Chiura Obata: An American Modern (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2018, also an exhibition); and Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo (Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 2023, also an exhibition). ↩︎

-

Wang, The Other American Moderns, 2. ↩︎