On December 17, 1944, the West Coast exclusion ban was lifted, effective January 2, 1945. Over the course of the coming year, all ten of the WRA incarceration camps would begin to close.1 On June 11, 1945, the Ueyamas left Amache.2

A few years after their return to Los Angeles, Tokio and Suye

opened the gift store Bunkado in the heart of Little Tokyo.

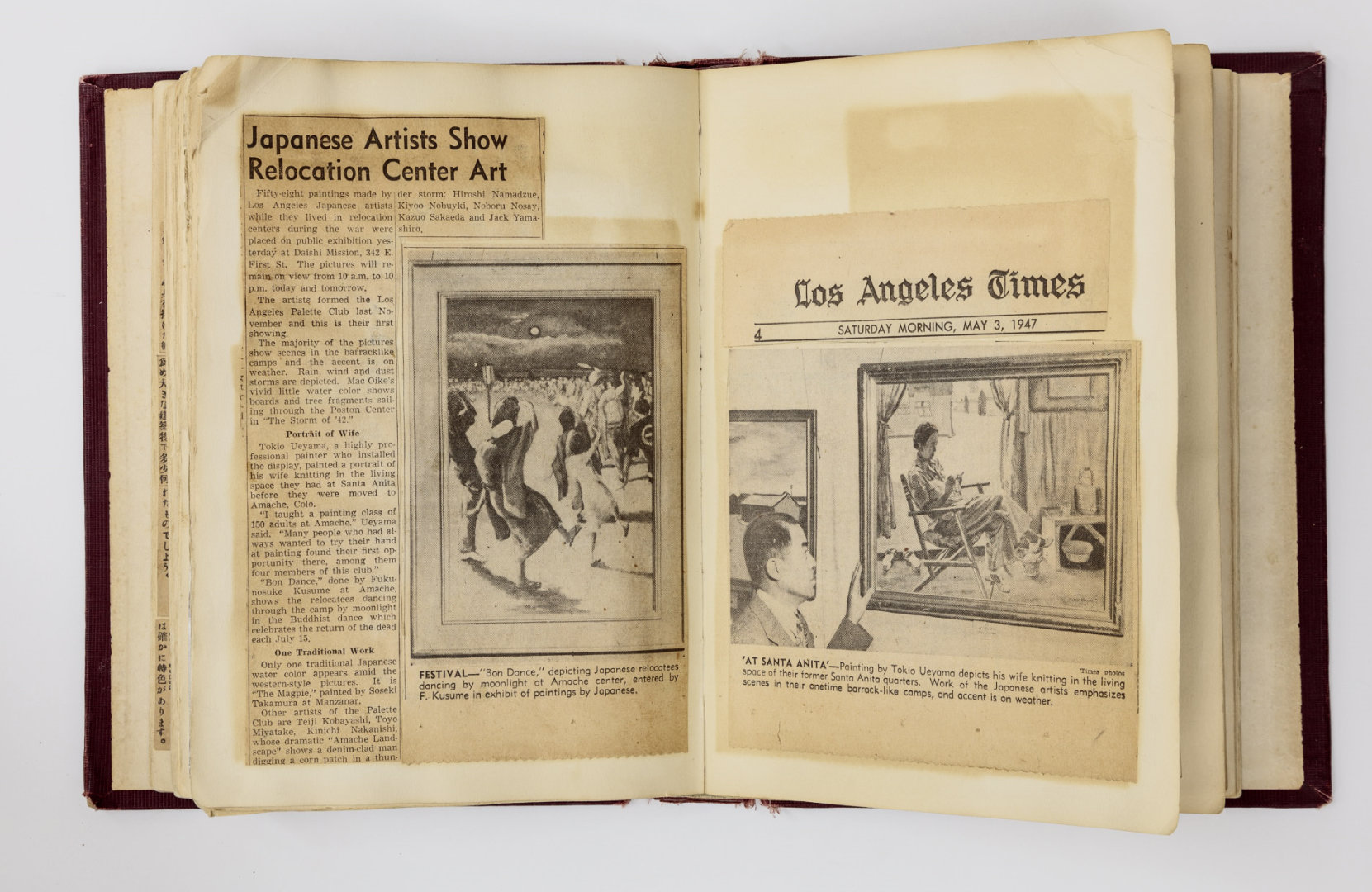

Tokio worked to help rebuild the artistic community, forming

the Los Angeles Palette Club with a group of artists in

November 1946.3

The Palette Club hosted annual exhibitions in Little Tokyo

over the coming years. In the exhibitions held in 1947 and

1948, Ueyama exhibited work from Amache, including

The Evacuee, a scene from the Manzanar War Relocation Center in

California (which he had visited in September 1945), and

Japanese subjects (fig. 1). He played a leadership role,

serving as chairman of the spring 1947 and 1948

exhibitions.4

The Evacuee, a scene from the Manzanar War Relocation Center in

California (which he had visited in September 1945), and

Japanese subjects (fig. 1). He played a leadership role,

serving as chairman of the spring 1947 and 1948

exhibitions.4

Ueyama curtailed his art production into the late 1940s.5 He died on July 12, 1954, aged sixty-four. Family member David Hirai recalls that Ueyama’s funeral was full to overflowing.6 In the catalog for his memorial exhibition, Sasabune Sasaki remembered the artist as “a gentle and solid person who loved peace and solitude,” a man of “unshakeable convictions,” and one who stayed true to his artistic philosophy in search of peace, calmness, and quietude.7

Suye continued to manage Bunkado and died on March 12, 1969, aged seventy-one. The store still thrives in the heart of Little Tokyo, now owned and operated by Irene Tsukada Simonian, Tokio and Suye’s niece, and managed by Dane Ishibashi, the Ueyamas’ great grand-nephew. Ueyama’s artwork can still be seen displayed among the store’s products, as it was during his lifetime (fig. 2).8

It has taken many years for the United States to reckon with the unconstitutional forced relocation of Japanese Americans during World War II. The rise of civil rights activism in the 1960s and extensive efforts by the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) in the 1970s helped lead to President Gerald Ford’s formal act rescinding Executive Order 9066 in 1976. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter established the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), which found that the causes for forced relocation were “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.”9 The Civil Liberties Act of 1988, signed by President Ronald Reagan, granted $20,000 and a formal presidential apology to every surviving Japanese American incarcerated during World War II.10

Due to efforts by people formerly incarcerated and their families starting in the 1960s, Amache achieved status as a national historic site in March 2022.11 In February 2024, the site officially became part of the National Park system after decades of volunteer management driven by the Friends of Amache group, the town of Granada, and the Amache Preservation Society established by educator John Hopper and supported by his students.12 The University of Denver has also played a leading role in understanding and excavating the site, particularly thanks to the work of archaeologist Bonnie Clark and her students.13 Not least of these efforts, family and friends have made regular pilgrimages to Amache since 1975. These continue to take place, typically in May during the weekend before Memorial Day.14

Because of these efforts, Amache’s legacy as a place of remembrance and education is ensured. Ueyama’s work sheds light on the lived experience of Amache, on the consequences of forced relocation, and on the important role of the arts in nurturing resilience, agency, and identity. As a whole, Ueyama’s life helps reveal untold histories, and his oeuvre stands the test of time as a significant contribution to American art.

-

Tule Lake marked the last camp to close, on March 20, 1946. See Robert Harvey, Amache: The Story of Japanese Internment in Colorado during World War II (Scottsdale, AZ: Hawes & Jenkins, 2023), 283. ↩︎

-

Many incarcerated people felt complicated feelings of both relief and fear when leaving camp, having experienced anti-Japanese sentiment outside its barbed wire fences. See Harvey, “Going Home,” in Amache, 263–83. ↩︎

-

See “Japanese Artists Show Relocation Center Art,” Los Angeles Times, May 4, 1947. ↩︎

-

See Mary Oyama, “Reveille,” May 2, 1947, clipping in scrapbook, Collection of Bunkado, Inc.; and undated clipping, “Attn: Nisei artists,” scrapbook, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

Family member David Hirai remembers that Tokio may have developed some eye trouble at this time. Conversation with the author, as told to Hirai by Suye Ueyama, April 2023. Ueyama’s memorial exhibition catalog identifies Autumn Fruit from 1947 (no. 16) as his last painting. See Memorial Exhibition catalog, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

Conversation with the author, April 2023. ↩︎

-

See Memorial Exhibition catalog, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

Bunkado website, accessed November 28, 2023, https://www.bunkadoonline.com/pages/new. ↩︎

-

See the National JACL Power of Word II Committee, The Power of Words Handbook: A Guide to Language about Japanese Americans in World War II (Japanese American Citizens League, 2013, revised 2020), 6 and the Densho Encyclopedia on the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Commission_on_Wartime_Relocation_and_Internment_of_Civilians/. ↩︎

-

See the Densho Encyclopedia on the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Civil Liberties Act of 1988. ↩︎

-

President Joe Biden signed the Amache National Historic Site Act into law on March 18, 2022. For press on the site’s management history, see Kevin Simpson, “Amache Is on the Verge of Earning National Park Status,” Colorado Sun, February 14, 2022, https://coloradosun.com/2022/02/14/amache-on-verge-national-historic-site/. ↩︎

-

See “Amache Preservation Society,” accessed November 29, 2023, Amache.org, https://amache.org/amache-preservation-society/. For information on the project team, see “Project Team,” accessed November 29, 2023, Amache.org, https://amache.org/project-team/. ↩︎

-

See the DU Amache Research Project, accessed November 29, 2023, https://portfolio.du.edu/amache. ↩︎

-

On the pilgrimage, see “Pilgrimage History,” accessed November 29, 2023, Amache.org, https://amache.org/pilgrimage-history/ . ↩︎