1889–1908, Early Life

Tokio Ueyama is born on September 22, 1889, in Toyajo, Wakayama Prefecture, to parents Sojuro and Hamaye Nakai Ueyama. His Japanese education includes Toyajo Elementary School, Taikuy Junior High School, Prefecture High School, and Eastlake English School. While studying at Eastlake, he works for the design department of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office in Tokyo.1

In April 1908, a nearly eleven-year-old Suyeko “Suye” Tsukada (1897–1969) leaves Japan on the ship Iyo Maru with her father, Tomojiro Tsukada, and mother, Hana Uyeda Tsukada, and arrives in Seattle on April 17.2 (Twenty years later, Suye marries Tokio in California.)

Ueyama arrives at Seattle, Washington, on May 7, 1908, after sailing from Yokohama on the ship Kaga Maru.3

1909–21, American Art Education

In November 1909, Ueyama enrolls at the California School of Design (later renamed the San Francisco Art Institute) and leaves in February 1910.4

On April 6, 1910, Ueyama’s mother dies. He is twenty years old.5

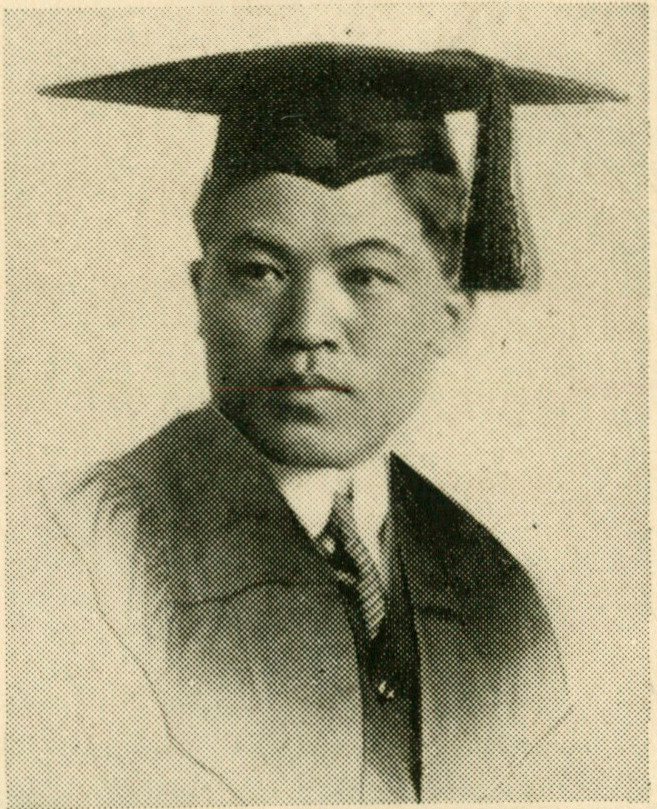

In 1910, Ueyama enrolls in the painters’ course at the University of Southern California, graduating with a degree in fine arts in 1914 (fig. 1).6

The 1913 Alien Land Laws in California and Arizona prohibit Asian immigrant males from purchasing or owning land.7

In 1916, Ueyama is included in the Southern California Japanese Art Club exhibition at the Nippon Club in Los Angeles, his first recorded exhibition.8

In 1917, Ueyama moves to the East Coast and studies at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia until 1921.9

In June 1918, he receives an honorable mention at PAFA for his work in perspective.10

In November 1919, he exhibits in the

Third Exhibition of Work Done at Chester Springs, the

Summer School of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine

Arts.11

Works on display include a painting of a sculpture bust

exhibited as

Head

(no. 2 in the catalog), The Spring House (no. 32),

The Hills (no. 103), and Portrait (no.

124).

Head

(no. 2 in the catalog), The Spring House (no. 32),

The Hills (no. 103), and Portrait (no.

124).

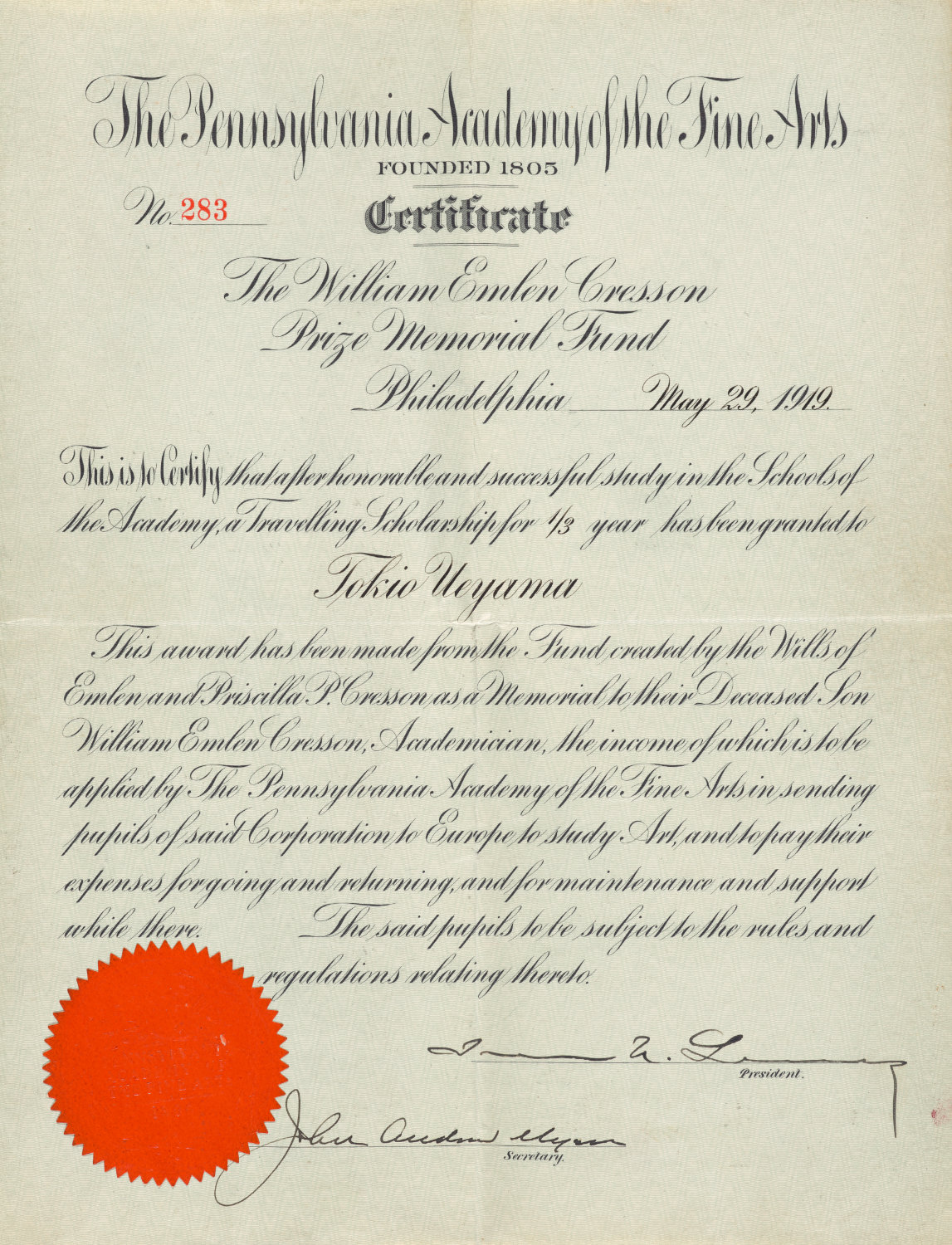

In 1919, he wins a $500

William Emlen Cresson Memorial Travel Scholarship

to fund three months of travel abroad.

William Emlen Cresson Memorial Travel Scholarship

to fund three months of travel abroad.

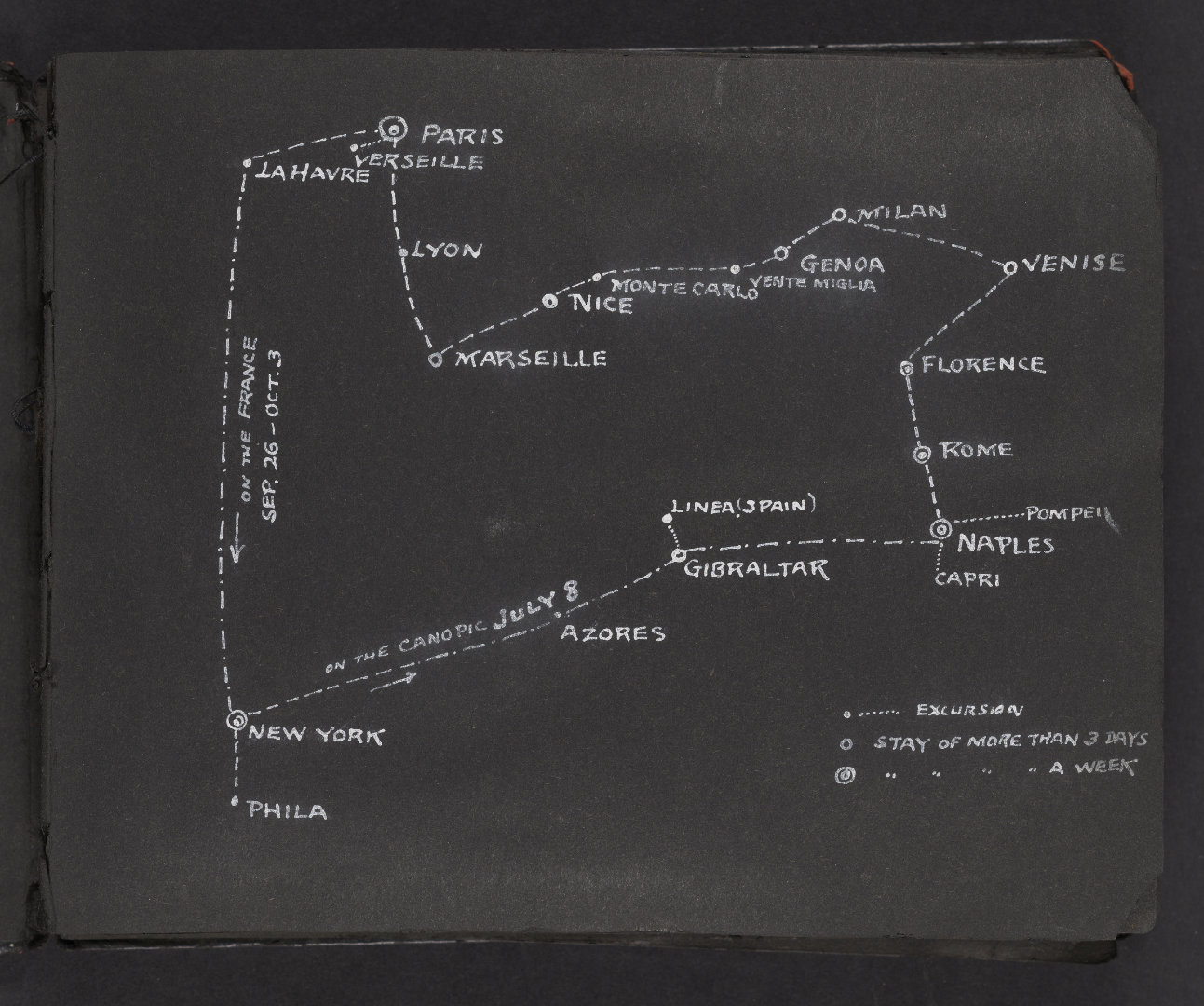

On July 8, 1920, Ueyama leaves New York City on the ship Canopic headed to Europe for his Cresson scholarship summer (fig. 2).

The Canopic makes a brief stop at the Azores, then carries on to Gibraltar, where Ueyama stays for multiple days and takes a short excursion north into Spain. The ship then carries on to Naples, where he disembarks and stays for more than a week, taking excursions to Capri and Pompei. From Naples, Ueyama travels by train to Rome, where he stays for over a week. From Rome, he takes the train to Florence, where he stays for more than a week, before moving to Venice for several days. From there, he travels to Milan, Genoa, Nice, and Marseille, staying multiple days at each and making shorter stops in Ventimiglia and Monte Carlo. From Marseille, he takes a train to Paris, where he stays more than a week. From Paris, he takes a train to Le Havre and embarks on the SS France on September 26, arriving in New York on October 4.12

Ueyama completes his studies at PAFA in 1921.

1922–41, California, Oregon, Mexico, and Japan

He probably returns by train to Los Angeles in January 1922, departing Philadelphia on January 8 to Kansas City, then San Francisco, arriving in Los Angeles on January 12.13

In 1922, Ueyama cofounds the association Shaku-do-sha with artists Hojin Miyoshi (1888–unknown) and Sekishun Masuzo Uyeno (c. 1892–unknown) and poet T. B. Okamura (dates unknown).

From April 21 to May 28, 1922, Ueyama exhibits The Spring House (no. 64 in the catalog) and Portrait Study (no. 65) in the Third Exhibition: Painters and Sculptors of Southern California, Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art.14

From November 17 to December 16, 1922, he exhibits Summer Girl (no. 90 in the catalog), Fur Coat (no. 91), and Lake Arrow Head (no. 92, illustrated) at the second exhibition of the East West Art Society at the San Francisco Museum of Art at the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco.15

From May 4 to June 17, 1923, Ueyama exhibits The Fur Coat (no. 67 in the catalog) in the Fourth Exhibition: Painters and Sculptors of Southern California, Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art.16

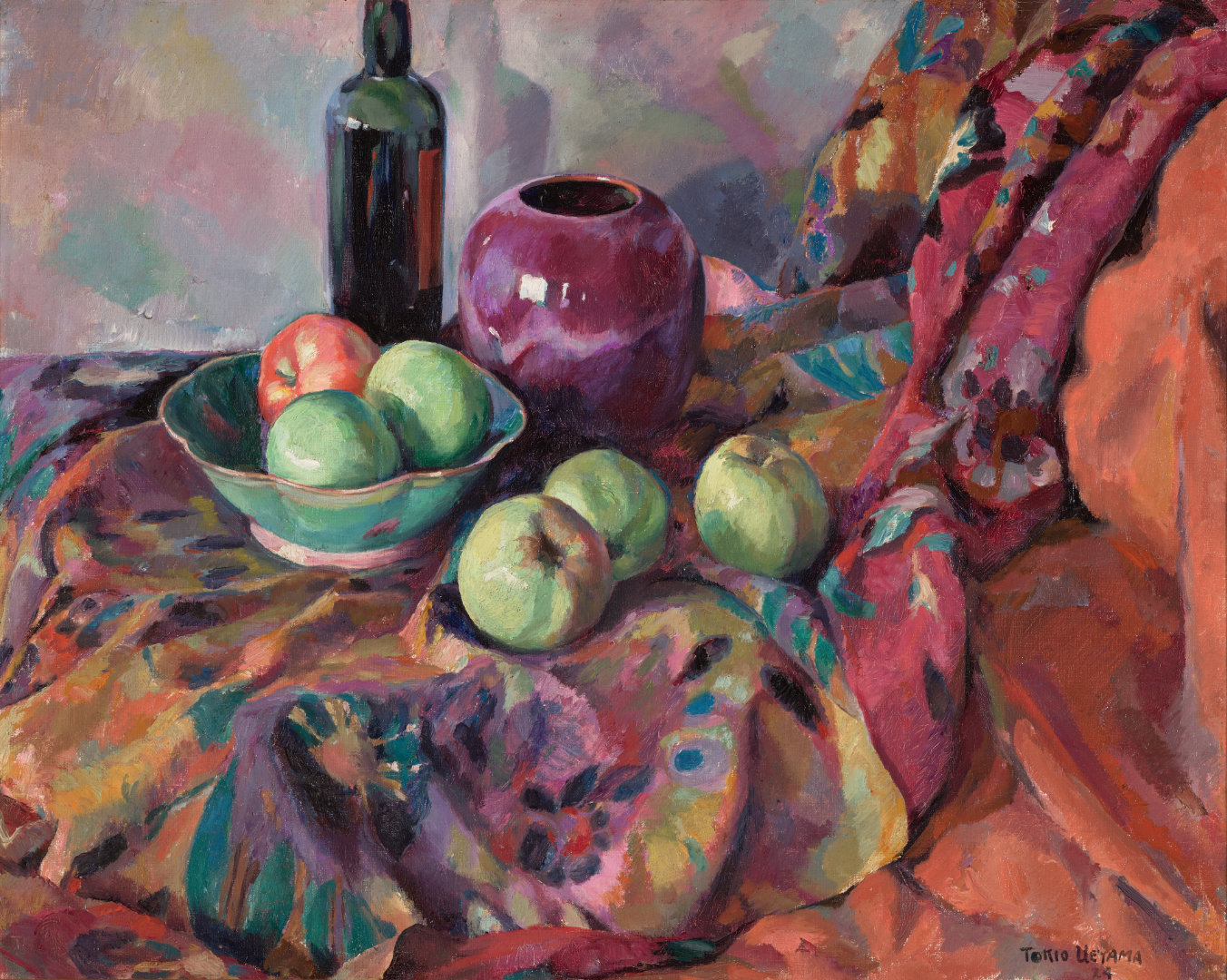

Between June 15 and 28, 1923, the Shaku-do-sha holds its first group exhibition at the Japanese Union Church at 120 N. San Pedro Street. Ueyama exhibits four paintings: Still Life (no. 21 on the checklist), Still Life (no. 22, illustrated), Portrait Sketch (no. 23), and Spring in the Valley (no. 24).17 Ueyama also contributes a woodblock print for the cover of the catalog.18

On September 1, 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake strikes south of Tokyo, bringing down buildings and piers. Its tremor creates a tsunami that sweeps away thousands of people. Fires rage until September 3, devastating Tokyo and Yokohama. According to a later news report, Ueyama had sent paintings by ship to Japan for a government exhibition that were lost in the disaster.19

Congress passes the Immigration Act of 1924 (Johnson-Reed Act), which halts all immigration from Asia and limits other immigrants through a national origins quota.20

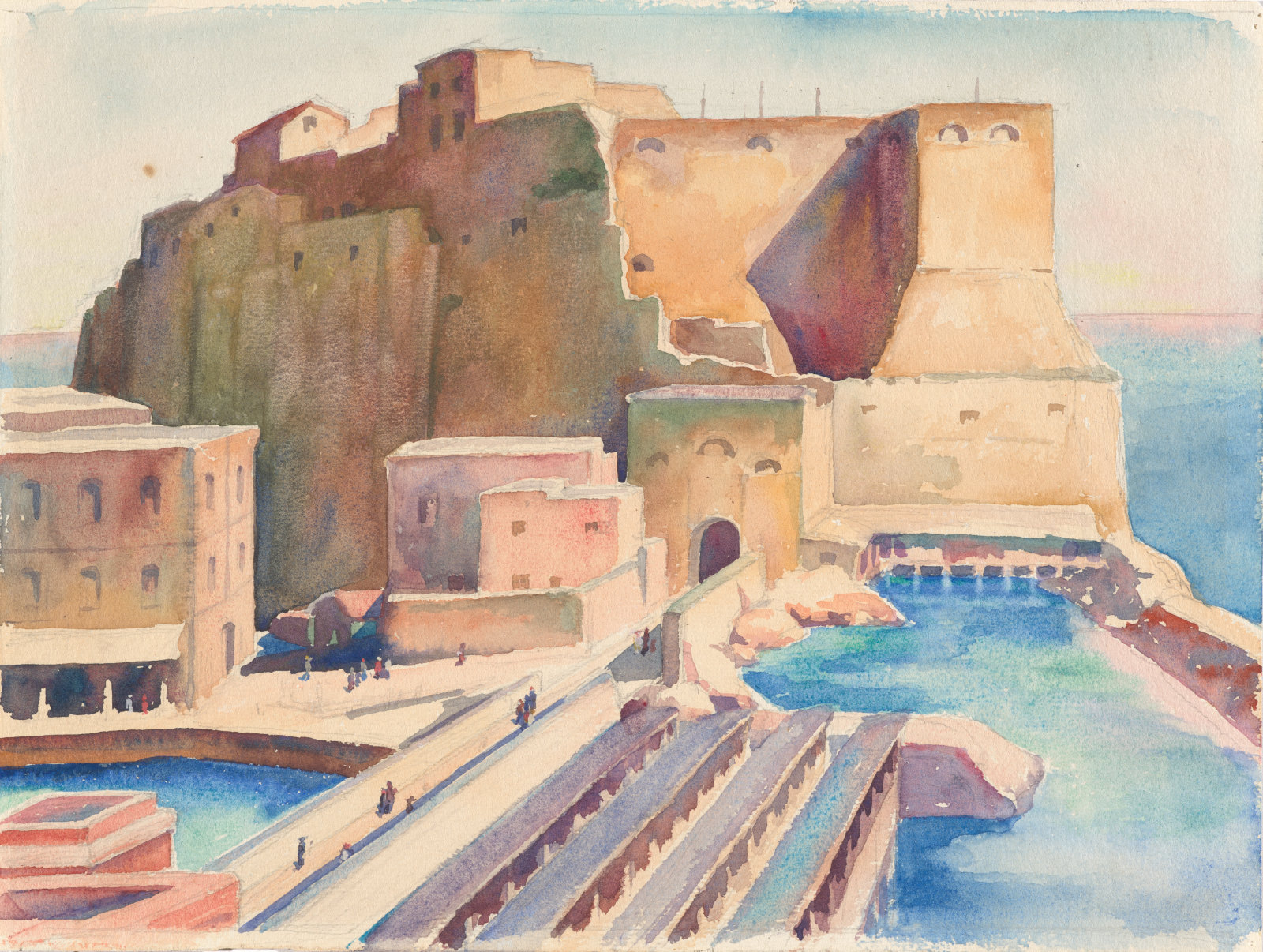

From September 20 to 30, 1924, Ueyama mounts his first known

solo exhibition at the Sumida Music Store at 325 East First

Street. Among the twenty-five works exhibited are his

watercolor

The Castle in Naples

(no. 13 in the catalog), his early

The Castle in Naples

(no. 13 in the catalog), his early

Self Portrait

(no. 25), and possibly

Self Portrait

(no. 25), and possibly

Still Life

(no. 10 or 19). It is also possible that a

Still Life

(no. 10 or 19). It is also possible that a

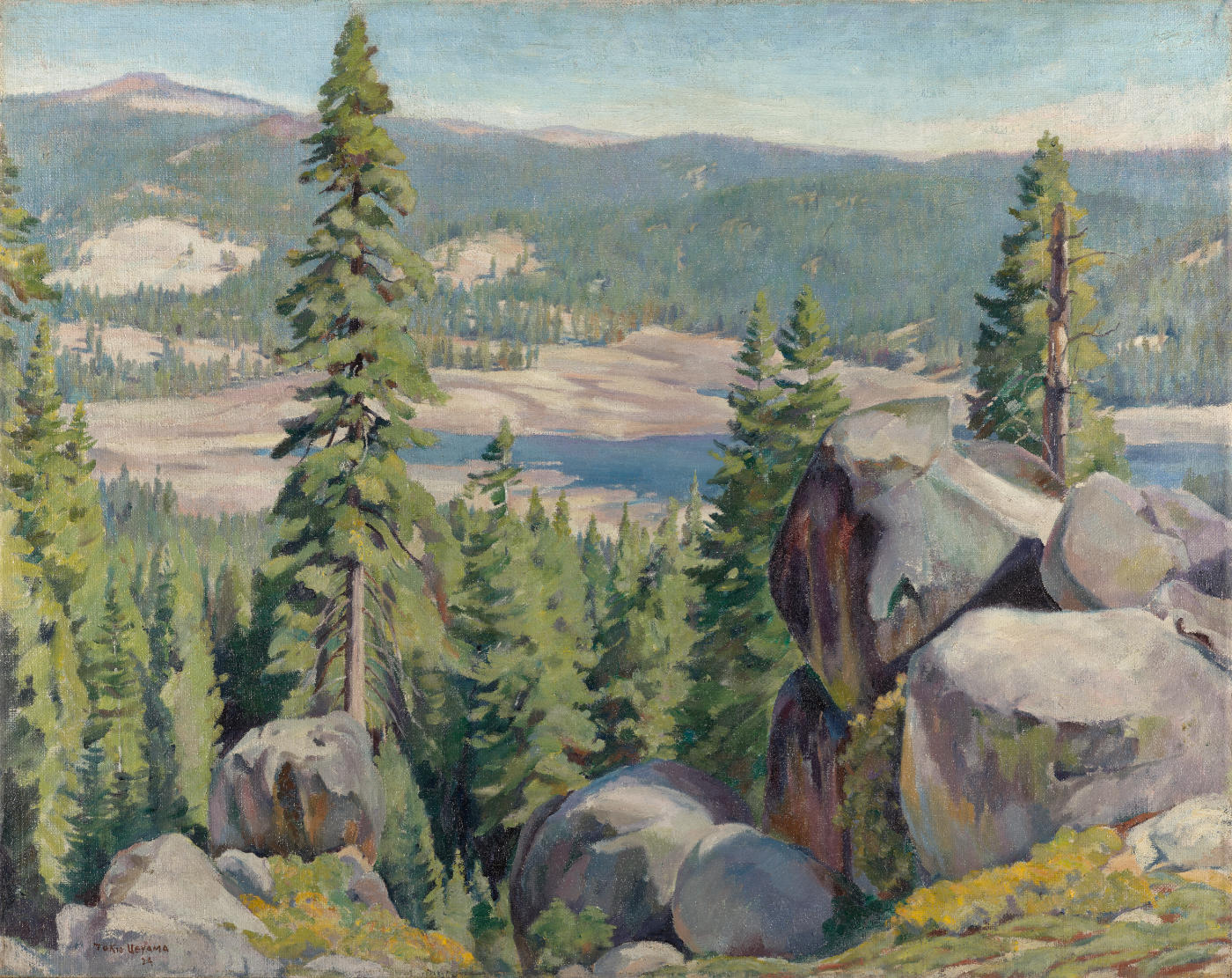

currently untitled California landscape

dated 1924 was exhibited as

In the High Sierras (no. 23).21

currently untitled California landscape

dated 1924 was exhibited as

In the High Sierras (no. 23).21

In November 1924, Ueyama presents a one-man exhibition of twenty-five works at the gallery at the University of Oregon in Eugene. His friend and PAFA classmate Nowland B. Zane (1885–1945), a professor at the university, probably invited him to exhibit.22

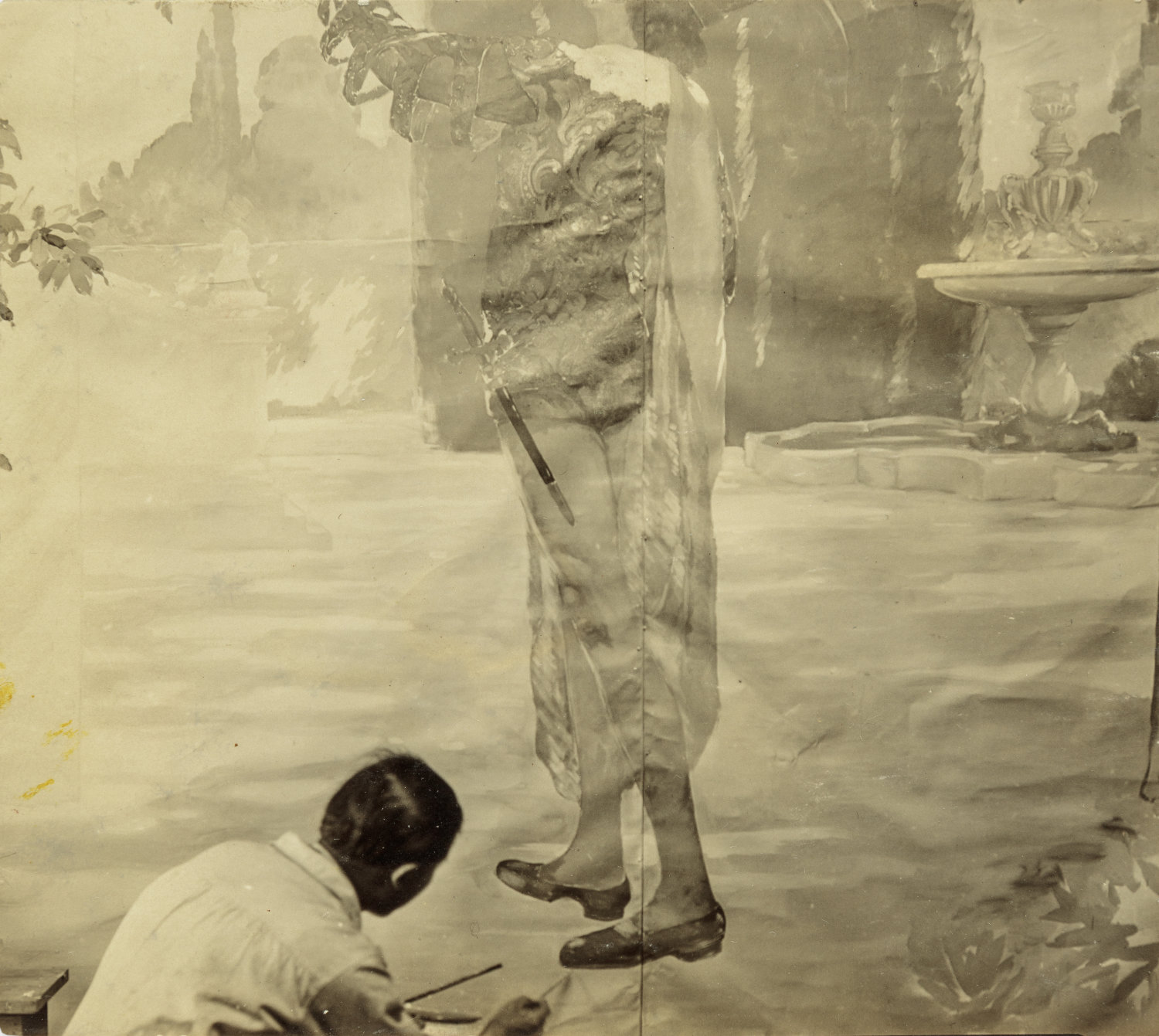

In 1924, Ueyama is commissioned to create murals of Romeo and Juliet and Macbeth for the Elsinore Theatre in Salem, Oregon. Currently, these are attributed to Zane and may have been a shared commission (fig. 3).23 The Elsinor Theater opened to the public on May 28, 1926.

In April 1925, Ueyama exhibits Portrait of Miss B. (no. 73 in the catalog) at the Sixth Exhibition: Painters and Sculptors of Southern California, Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art.24

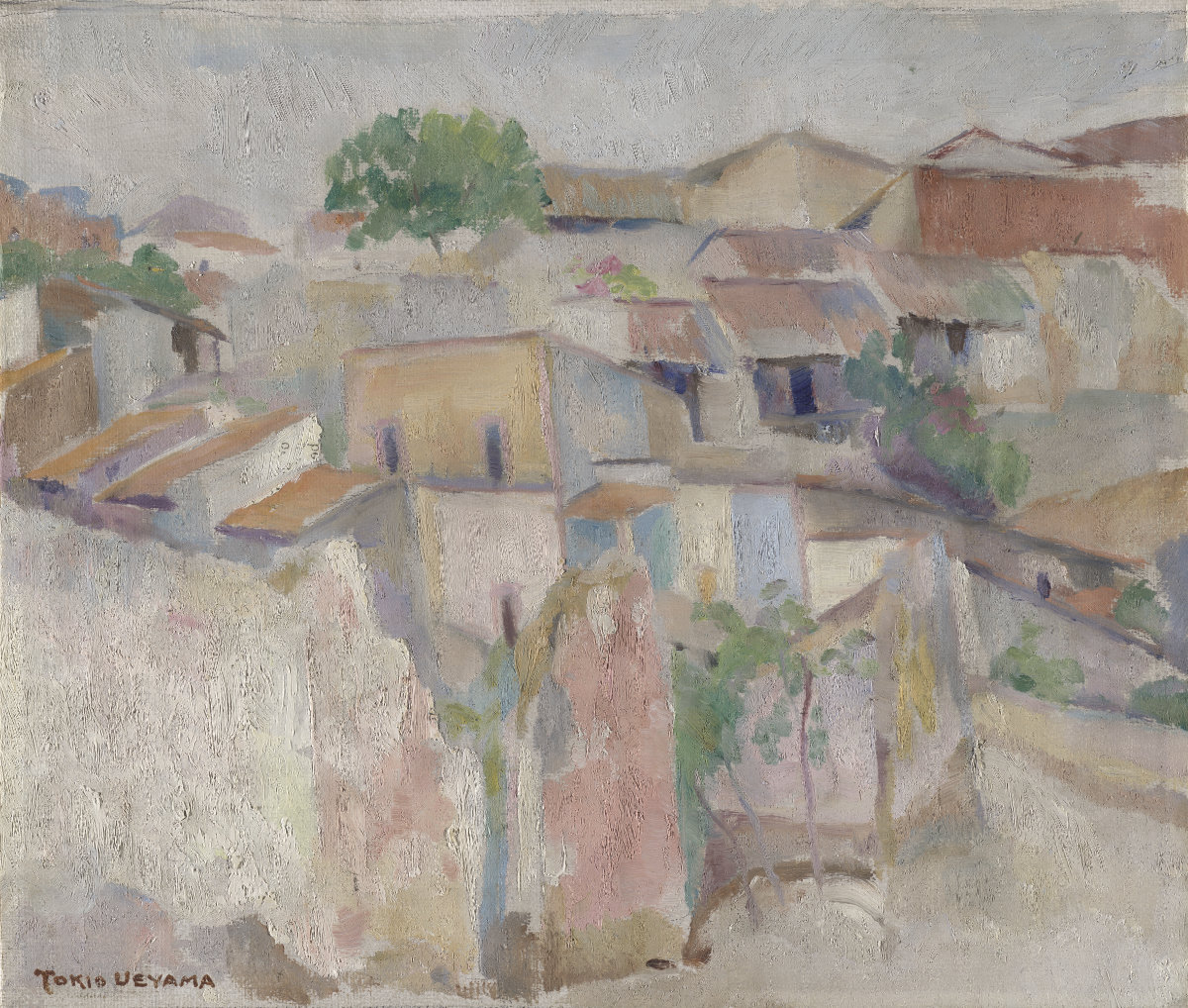

On May 24, 1925, Ueyama passes through the US border at El Paso, Texas, for a three-month sojourn in Mexico. He passes back into the US on August 27.25 While in Mexico, he spends time in Mexico City, Cuernavaca, and Taxco. He meets Diego Rivera, Jean Charlot, and probably Edward Weston.26

Ueyama probably travels back to Oregon in 1925.27

A letter dated February 13, 1926, from F. T. Iwakura in Courtland, California, is addressed to Ueyama at 1912 Moss Street in Eugene, Oregon, suggesting he was in Oregon at that time.28

From April 9 to May 23, 1926, Ueyama exhibits Creeping Shadows (no. 62 in the catalog) in the Seventh Exhibition: Painters and Sculptors of Southern California, Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art.29

In late May 1926, Ueyama helps arrange stage decorations with Zane at the University of Oregon for an upcoming dance drama.30

During the summer of 1926, Ueyama wins an honorable mention for his painting The Spring-house when it is exhibited (no. 143 in the catalog) in the first annual Southern California Artists’ exhibition at the Fine Arts Gallery, San Diego, from June 4 to August 31.31

Later in 1926, he exhibits at the Southern California State Fair in Riverside County and wins honorable mention for Still Life.32

In January 1927, Ueyama begins working for the Bunrindo Book Store at 303 East First Street in Los Angeles.33

From April 6 to May 17, 1928, Ueyama exhibits

Portrait in Black

(no. 83 in the catalog) at the Ninth Exhibition:

Painters and Sculptors of Southern California, Los

Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art.34

Portrait in Black

(no. 83 in the catalog) at the Ninth Exhibition:

Painters and Sculptors of Southern California, Los

Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art.34

On July 23, 1928, Ueyama marries Suye Tsukada in a ceremony at California’s Mission Inn led by Reverend Taizo Kitagawa (fig. 4).35

From April 14 to 28, 1929, Ueyama exhibits Portrait Study in Black (no. 158 in the catalog) in the 51st San Francisco Art Association exhibition.36

From June 7 to August 31, 1929, he exhibits Creeping Shadows (no. 93 in the catalog) in the Fourth Annual Exhibition of Southern California Art at the Fine Arts Gallery of San Diego.37

In December 1929, Ueyama exhibits two paintings in the first

annual Japanese Artists of Los Angeles exhibition

held at the Rafu Nichibei Art Salon at 219 N. San Pedro

Street. Based on a review written by Arthur Millier, art

critic for the LA Times, these were probably

Monterey

and

Monterey

and

Portrait in Black.38

Portrait in Black.38

In 1930, Tokio and Suye move to the Fulsom Street house owned by Mr. and Mrs. Wilson.39

From April 4 to May 25, 1930, Ueyama exhibits a painting titled Monterey (no. 96 in the catalog) in the Eleventh Exhibition: Painters and Sculptors of Southern California, Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art.40

Later in 1930, he exhibits in the second annual Japanese Artists of Los Angeles.41

In 1931, Ueyama exhibits

Church at Taxco, Mexico (no. 440 in the catalog) in

the 53rd exhibition of the San Francisco Art Association at

the Palace of the Legion of Honor from April 26 to May

31.42

Ueyama painted a number of versions of the Church of Santa

Prisca de Taxco. While it is unknown which one was on

display in San Francisco, it may have been similar to the

oil included in the exhibition

accompanying this catalog.

oil included in the exhibition

accompanying this catalog.

From April 25 to June 6, 1935, Ueyama exhibits one painting, The Rain (no. 104 in the catalog), in the Sixteenth Annual: Painters and Sculptors of Southern California, Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art.43

From February 19 to 24, 1936, Ueyama holds a significant

solo exhibition composed of sixty-one works at the Miyako

Hotel on First and San Pedro Streets.

The Nude

(no. 6 in the catalog) is illustrated on the cover of the

catalog. Also included were

The Nude

(no. 6 in the catalog) is illustrated on the cover of the

catalog. Also included were

Portrait in Black

(no. 14),

Portrait in Black

(no. 14),

Self Portrait

(no. 21),

Self Portrait

(no. 21),

Red Rock Canyon

(no. 40), and

Red Rock Canyon

(no. 40), and

At Cuernavaca

(no. 60).44

At Cuernavaca

(no. 60).44

On February 28, 1936, Ueyama receives a letter from the LA Art Association appointing him as its envoy to Japan to develop relationships that might result in exhibitions of Japanese artwork in California and of California artwork in Japan.45

Ueyama receives his travel permit on March 10, 1936, and leaves on the ship Asama on May 30.46 While intending to stay for only ten months, he applies for an extension with the American consulate at Yokohama on February 1, 1937, and stays for a total of thirteen months.47 While in Japan, he mounts a solo exhibition at his alma mater, Toyajyo Elementary School.48

On April 28, 1937, Tokio, Suye, Tokio’s father, Sojuro, and Suye’s brother Jutaro Narumi board the SS Tatsuta Maru in Yokohama bound for San Francisco, where they arrive on May 12, 1937. Two days later, they arrived on the same ship at San Pedro and the port of Los Angeles.49

Ueyama’s father dies unexpectedly of a stroke in December 1939.50

The following month, January 1940, Suye’s father dies of a stroke.

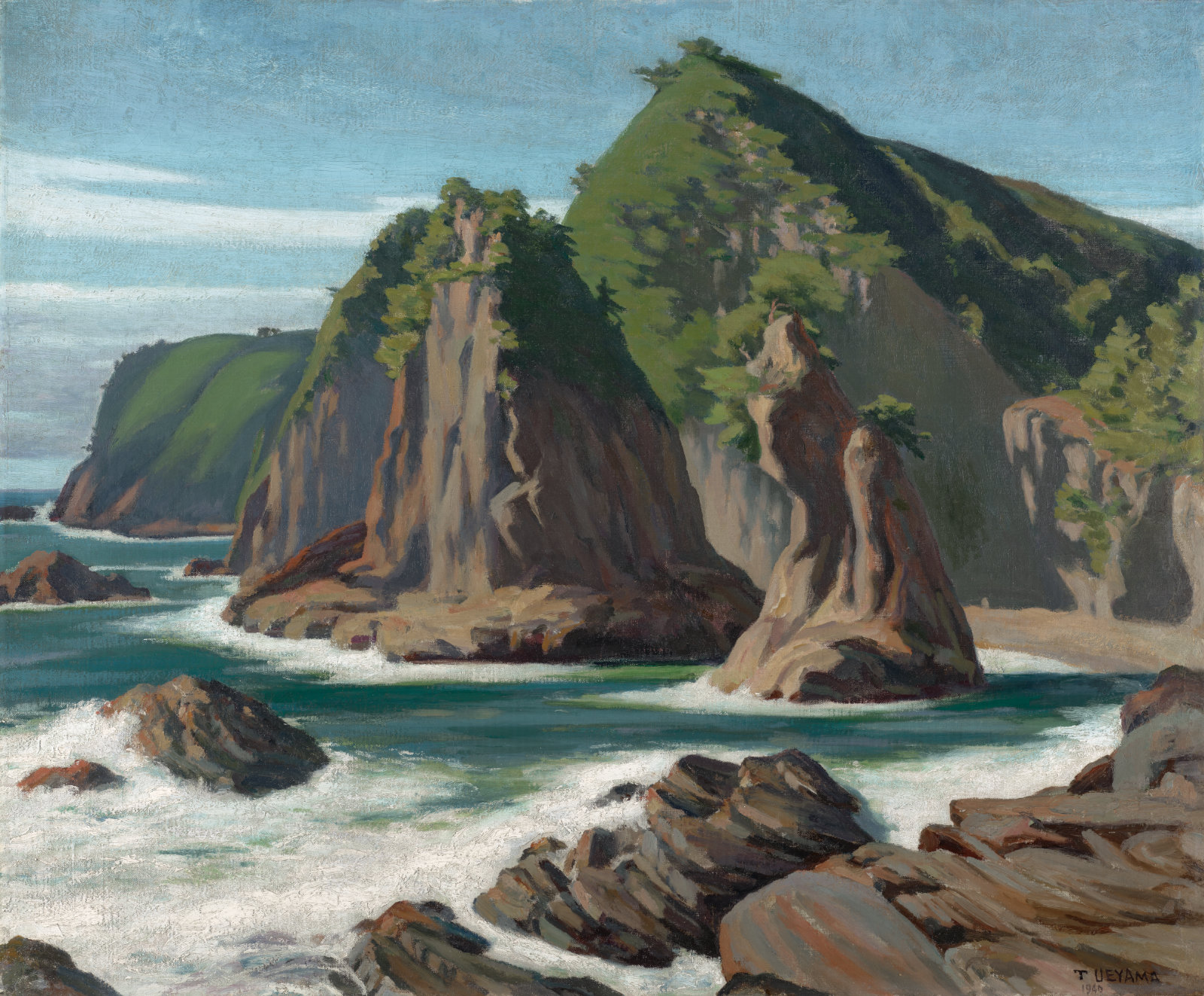

From May 25 to September 29, 1940, Ueyama exhibits Misumi, Japan (no. 2165 in the catalog) and The Rain (no. 2166) in California Art Today at the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco.51

Between July 19 and 22, 1940, Ueyama writes in his diary that he and Suye travel to San Francisco with Mr. and Mrs. Wilson. They stop in Monterey and drive up the Pacific Coast Highway. They visit the Presidio, Golden Gate State Park, and Chinatown. The Wilsons returned to LA, but Suye and Tokio remain to visit the Golden Gate International Exposition.52

On September 27, 1940, Germany, Italy, and Japan sign the Tripartite Pact formalizing the alliance between the three countries. Ueyama notes Japan’s having joined the Axis in his diary that same day.53

On August 31, 1941, Ueyama writes in his diary that he has quit working for Bunrindo, where he has worked for fourteen years. “My heart is heavy with feeling.”54

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacks Pearl Harbor. In response, the US joins World War II.

1942–45, World War II and Amache

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066, allowing for the mass incarceration of over 120,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast during WWII without trial or hearings.55

On March 18, 1942, President Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9102, establishing the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to formulate a program for Japanese relocation.

The Santa Anita Assembly Center, a temporary detention center where the Ueyamas are first detained, opens on March 27, 1942. (It closes on October 27, 1942).

On June 12, 1942, construction of the WRA-managed Granada Relocation Center in Colorado, colloquially known as Amache (pronounced ah-mah-chee), begins. It is in operation by August and sees its maximum population that October at 7,318. More than 10,000 people are incarcerated at Amache over time.56

Also on June 12, 1942, the 100th Infantry Battalion—a segregated unit composed of second-generation Japanese Americans (Nisei)—is activated.57

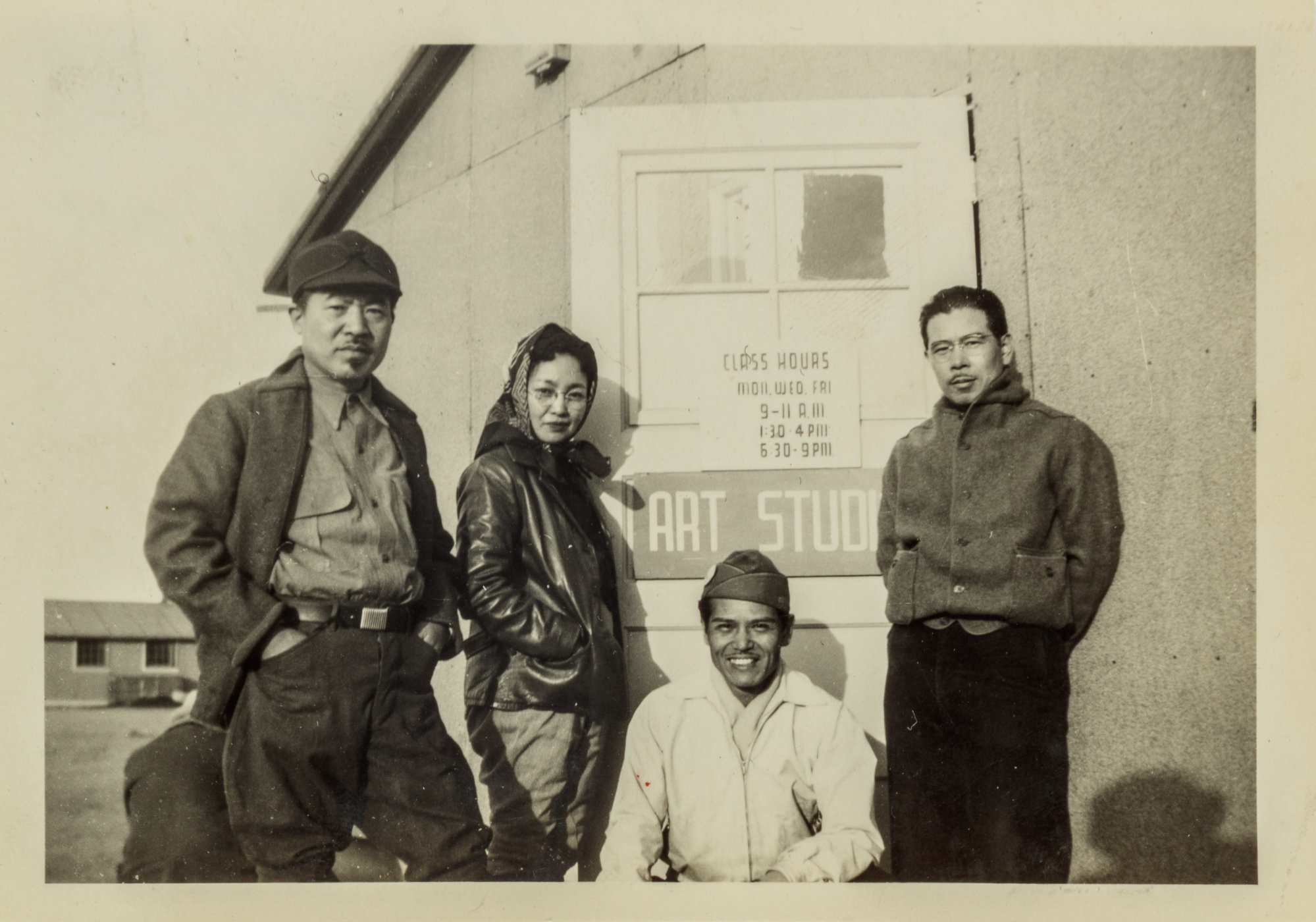

The Ueyamas arrive at Amache on September 19, 1942, and reside at barrack 6F-7C.58 With Koichi Nomiyama (1900–1984) and others, Ueyama supervises and teaches art classes three times a day, three days a week, in the 7E block recreation hall (fig. 5).59

On February 1, 1943, President Roosevelt activates the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a segregated regiment of Japanese Americans.60 On August 10, 1944, the 100th Infantry Battalion is integrated into the 442nd.61 These remain the most decorated units of their size in US military history.62 Thirty-one members of Amache are killed at war.63

In March 1943, Ueyama exhibits

The Evacuee

at the Arts and Crafts Festival at Amache held in Terry

Hall.64

The Evacuee

at the Arts and Crafts Festival at Amache held in Terry

Hall.64

On December 17, 1944, the West Coast exclusion ban is lifted, effective January 2, 1945.65 The ten concentration camps run by the WRA begin to close.

On May 29, 1945, Ueyama receives permission to travel to Los Angeles.66

On June 11, 1945, the Ueyamas leave Amache.67

On August 31, 1945, Ueyama receives permission to travel to the Manzanar Relocation Center, California. He departs Los Angeles on September 4 and returns on September 20.68

The last residents leave Amache on October 15, 1945.69

1946–69, Los Angeles

In November 1946, a group of artists including Ueyama form the Los Angeles Palette Club.70

In 1947, Suye and Tokio open the gift shop Bunkado (fig. 6).71

From May 2 to 4, 1947, Japanese artists of the LA Palette

Club exhibit artwork created at American concentration camps

at the Daishi Mission, or Koyasas Beikoku Betsuin, on 342

East First Street. Ueyama exhibits

At Santa Anita (known as

The Evacuee, no. 48 in the catalog), Yucca Trees (no. 49),

Amache Center (no. 50),

Passing Shower (no. 51),

Our Corn Patch (no. 52), Cactus (no. 53),

and Manzanar (no. 54). Ueyama serves as chairman of

the exhibition.72

The Evacuee, no. 48 in the catalog), Yucca Trees (no. 49),

Amache Center (no. 50),

Passing Shower (no. 51),

Our Corn Patch (no. 52), Cactus (no. 53),

and Manzanar (no. 54). Ueyama serves as chairman of

the exhibition.72

From November 5 to 10, Ueyama exhibits

Self Portrait (no. 33), possibly this

self-portrait, Katsuura (no. 34 in the catalog), possibly

self-portrait, Katsuura (no. 34 in the catalog), possibly

this painting, and Still Life (no. 35) in the Los Angeles

Palette Club’s Second Annual Exhibition at the

Daishi Mission.73

this painting, and Still Life (no. 35) in the Los Angeles

Palette Club’s Second Annual Exhibition at the

Daishi Mission.73

From September 29 to October 4, 1948, Ueyama exhibits The Spring Light (no. 37 in the catalog), Sketch (no. 38), and Amakusa, Japan (no. 39) in the LA Palette Club’s Third Annual Exhibition at the Daishi Mission. Ueyama serves as chairman of the exhibition.74

In 1952, Congress passes the McCarran-Walter Act, allowing Japanese immigration to the US again and allowing Issei (first-generation Japanese immigrants) to become US citizens for the first time.

Tokio Ueyama dies, aged sixty-four, on July 12, 1954.

Ueyama’s memorial exhibition takes place October 20 to 26,

1954, at the Japanese Chamber of Commerce of Southern

California, 358 East First Street. Thirty-five works are on

display representing the arc of his career, including

Portrait in Black

(no. 5 in the catalog),

Portrait in Black

(no. 5 in the catalog),

Red Rock Canyon

(no. 25), and Life at Santa Anita (known as

Red Rock Canyon

(no. 25), and Life at Santa Anita (known as

The Evacuee) (no. 27).75

The Evacuee) (no. 27).75

On March 12, 1969, Suye Ueyama dies, aged seventy-one, in Los Angeles.

-

See the biography (in Japanese) in Ueyama’s Memorial Exhibition catalog, 1954, Collection of Bunkado. Many thanks to Noriko Okada for translating the Japanese text. ↩︎

-

See handwritten note, small black notebook, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

See “Japanese Passport, 1908,” Tokio Ueyama papers, 1908–circa 1954, bulk 1914–1945, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-10; and handwritten note, small black notebook, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

See 1909–10 California School of Design college catalog and Ueyama registration documents shared in an email to the author from Jeff Gunderson, Archivist/Librarian of the SFAI Legacy Foundation + Archives, June 20, 2023. ↩︎

-

“Diary Excerpts Translated into English, 2023,” Tokio Ueyama papers, 1Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-9. ↩︎

-

See “University of Southern California Diploma,” Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-2-folder-8. ↩︎

-

See “Timeline of Japanese American History,” Japanese American National Museum, September 2021, https://www.janm.org/sites/default/files/2021-12/janm-education-resources-common-ground-previsit-timeline-and-vocabulary-2021.pdf. ↩︎

-

Gordon Chang, ed., Asian American Art: A History, 1850–1970 (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008), 439. This author has not located the source catalog for this exhibition. ↩︎

-

See registration cards at PAFA sent via email to the author from Hoang Tran, Director of Archives & Collections, PAFA, June 12, 2023. ↩︎

-

See hand-written letter dated June 28, 1918, red scrapbook, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

See Third Exhibition of Work Done at Chester Springs, the Summer School of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (Chester Springs, PA: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1919), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062805919&view=1up&seq=3. ↩︎

-

The ship manifest provides the date of arrival in New York as October 4, 1920. In a small black notebook in the Bunkado collection with his and Suye’s travel information, Ueyama notes the date as October 3. ↩︎

-

See Pullman train ticket stubs, “Visas and Other Travel Documents, 1920–1925,” Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-2-folder-9. ↩︎

-

See Third Exhibition: Painters and Sculptors of Southern California (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art, 1922), https://archive.org/details/calanhm_000570. ↩︎

-

The catalog is available at the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) in Los Angeles. ↩︎

-

See Fourth Exhibition: Painters and Sculptors of Southern California (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art, 1923), https://archive.org/details/calanhm_000590/mode/2up. ↩︎

-

I am grateful to Noriko Okada for her translation of the exhibition catalog, which is held at JANM. ↩︎

-

Woodblock print cover illustrated in Karin Higa, “Hidden in Plain Sight: Little Tokyo between the Wars,” in Asian American Art: A History, 1850–1970, 36. The original catalog is held at JANM. ↩︎

-

It is currently unknown which of his works perished. See “Japanese Art to be Shown in University Gallery Soon,” Oregon Daily Emerald, October 29, 1924, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1924-10-29/ed-1/seq-1/#words=Tokio+Ueyama. ↩︎

-

See “The Immigration Act of 1924 (The Johnson-Reed Act),” Office of the Historian of the United States Department of State, accessed November 9, 2023, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/immigration-act. ↩︎

-

The catalog is in the red scrapbook, 11, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

See “Japanese Art to be Shown in University Gallery Soon,” Oregon Daily Emerald, October 29, 1924, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1924-10-29/ed-1/seq-1/#words=Tokio+Ueyama; Margaret Skavlan, “Japanese Paintings Are Hung in University Art Gallery,” Oregon Daily Emerald, November 13, 1924, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1924-11-13/ed-1/seq-1/#words=Tokio+Ueyama; “Arts Club Will Open Exhibition with Tea,” Oregon Daily Emerald, November 18, 1924, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1924-11-18/ed-1/seq-3/#words=Tokio+Ueyama; “Exhibition of Japanese Artist’s Paintings Will Be Opened Today,” Oregon Daily Emerald, November 19, 1924, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1924-11-19/ed-1/seq-1/#words=Tokio+Ueyama; “Japanese Print Collector Visits Campus Today. S. Doi Paintings to be Presented With Ueyama Exhibition,” Oregon Daily Emerald, November 20, 1924, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1924-11-20/ed-1/seq-3/#words=Tokio+Ueyama; “Work of Japanese Artist Portrays Variety of Style,” Oregon Daily Emerald, December 2, 1924, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1924-12-02/ed-1/seq-1/#words=Tokio+Ueyama; and undated clipping, “Exhibit of Ueyama, Japanese Painter, Opens Wednesday,” red scrapbook, 8, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

Ueyama’s Memorial Exhibition biography states he received the commission in 1924, and a black-and-white photograph of Ueyama applying paint under Romeo’s shoe, illustrated in this timeline, provides incontestable evidence. See the Japanese version of his biography in the Memorial Exhibition catalog, 1954. I am grateful for a translation by Noriko Okada. I am also grateful to Kanae Aoki, whose research revealed that Ueyama helped create both murals, which still exist. See email to the author, December 18, 2023. Recently, Aoki co-curated Transbordering: Migration and Art Across Wakayama and the U.S.A at the Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama, Japan, which included artwork by Ueyama. ↩︎

-

See Sixth Exhibition: Painters and Sculptors of Southern California (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art, 1925), https://archive.org/details/calanhm_000621. ↩︎

-

His visa to visit Mexico was approved in Los Angeles on April 27, 1925. It shows that he entered Mexico on May 24, 1925, and was admitted back into the US on August 27, 1925. “Visas and Other Travel Documents, 1920–1925,” Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-2-folder-9. ↩︎

-

On his relationship with Diego Rivera, see “Tokio Ueyama: Un Pintor Japonés en México,” Revista de Revistas, September 6, 1925, 17–18 and 42. Page 42 is missing in the clipping available in the red scrapbook, 20–21, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. I am grateful to Memphis Despain for translating this article while ShiPu Wang’s research assistant in August 2022. Jean Charlot handwrote his address in Ueyama’s black notebook, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. The Shaku-do-sha later exhibited Weston’s work in 1925, 1927, and 1931 at the Sumida Music Store on East First Street. See Higa, “Hidden in Plain Sight,” 39. ↩︎

-

See “Talented Japanese Artist Visits Campus,” Oregon Daily Emerald, November 18, 1925, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1925-11-18/ed-1/seq-3/#words=Tokio+Ueyama; and “Dance,” Oregon Daily Emerald, April 2, 1926, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1926-04-02/ed-1/seq-4/. ↩︎

-

See “Correspondence—Miscellaneous, 1916–1936,” Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-4. ↩︎

-

See Seventh Exhibition: Painters and Sculptors of Southern California (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art, 1926), https://archive.org/details/calanhm_000633. ↩︎

-

See “Music to Add to Beauty of Dance Drama,” Oregon Daily Emerald, April 1, 1926, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1926-04-01/ed-1/seq-1/#words=Tokio+Ueyama; and “Dance Drama Has Atmosphere of Colorful and Dreamlike Fairyland,” Oregon Daily Emerald, April 2, 1926, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/2004260239/1926-04-02/ed-1/seq-1/. ↩︎

-

Catalog available in the archives of the San Diego Museum of Art. See also a clipping from the San Diego Independent, June 27, 1926, red scrapbook, 19, Collection of Bunkado, Inc; letter from Reginald Poland notifying of award, red scrapbook, 30, Collection of Bunkado, Inc; and Ione Rayburn, “Japanese Artists in California,” in “Sports and Vanities,” September 1927, clipping in red scrapbook, 37–38, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. Rayburn’s article states that Ueyama exhibited canvases at the Artland Club from December 1926 to January 1927, but to date this author has not found further references to these. ↩︎

-

Because he exhibited a number of paintings under this title, it is difficult to know which still life won the award. To date this author has not located the exhibition catalog. See references to this award and exhibition in Ueyama’s Memorial Exhibition biography; “Award Certificate from Southern California Fair, 1926,” Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-1; and Rayburn, “Japanese Artists in California.” ↩︎

-

“Diary Excerpts Translated into English, 2023,” Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-9. ↩︎

-

Catalog available in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) archives. ↩︎

-

See hand-written details in a small black notebook, Collection of Bunkado, Inc.; and a wedding expenses receipt, “Miscellaneous Biographical Information, circa 1928–1937,” Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-11. ↩︎

-

My thanks to ShiPu Wang for information on this exhibition. ↩︎

-

Catalog available in the archives of the San Diego Museum of Art. See also a clipping of an article by Reginald Poland, director of the Fine Arts Gallery, “Work in Annual Show of Virile, Positive Spirit,” red scrapbook, 5, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

Millier describes Monterey as “flooded with clear light which creates a fine pattern of light and shadow on headlands, houses, and blue water.” He continues: “His portrait of a young Japanese woman in black hat and coat holds one’s interest by its poise, feeling for textures and character.” Millier concludes by writing, “He is an accomplished and painstaking artist.” See Arthur Millier, “City’s Japanese Show Art,” Los Angeles Times, December 29, 1929. To date this author has not located the exhibition catalog. ↩︎

-

“Diary Excerpts Translated into English, 2023,” Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-9. ↩︎

-

Catalog available in the LACMA archives. ↩︎

-

To date, this author has not located the source catalog for this exhibition. Based on the review by LA Times art critic Antony Anderson, Ueyama had on display “an imposing and exceedingly skillful portrait of a young Japanese woman.” This might be his large portrait of Suye in a kimono painted in 1929 and now at the Japanese American National Museum. Anderson continues that Ueyama’s “strong modeling and understanding breadth of style show him to be one of our finest portrait painters, indeed, quite among the good portraitists of the country.” See clipping in red scrapbook, 15, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. Antony Anderson, “Art News From Laguna,” Los Angeles Times, December 21, 1930. ↩︎

-

Many thanks to ShiPu Wang for information about this exhibition. ↩︎

-

Catalog available in the LACMA archives. ↩︎

-

See catalog in red scrapbook, 30, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

“Correspondence—Miscellaneous, 1916–1936,” Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-4. ↩︎

-

See handwritten note in small black notebook, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

See handwritten note in small black notebook, Collection of Bunkado, Inc; and Japanese biography in his Memorial Exhibition catalog, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. I am grateful to Noriko Okada for her translation of the Japanese. ↩︎

-

See Memorial Exhibition catalog, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. I am grateful to Noriko Okada for her translation of the Japanese. ↩︎

-

See the manifest for the Tatsuta Maru; handwritten notes in small black notebook, Collection of Bunkado, Inc.; and “Visas and Other Travel Documents, 1920–1925,” Tokio Ueyama papers, rchives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-2-folder-9. I am grateful to Grace Keiko Nozaki for articulating family relationships. ↩︎

-

See Western Union telegraph dated December 10, 1929, “Correspondence—Ueyama Family, circa 1928–1939,” Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-7; and emails to the author from Grace Keiko Nozaki, June 19 and 20, 2023. ↩︎

-

This author has not located the source catalog and is grateful to ShiPu Wang for the information on this exhibition. In a diary entry from May 2, 1940, Ueyama writes that Misumi and Rain won citations. See “Diary Excerpts Translated into English, 2023,” Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-9. See also a letter from Timothy L. Pflueger, Vice Chairman, Golden Gate International Exposition, San Francisco, expressing gratitude for Ueyama’s participation, red scrapbook, 92–93, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

“Diary Excerpts Translated into English, 2023,” Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-9. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

See “Timeline,” Japanese American Museum of Art. ↩︎

-

On the history of Amache, see J. Burton, M. Farrell, F. Lord, and R. Lord, “Granada Relocation Center,” in Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites (Tuscon, AZ: Western Archeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, 2000), https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anthropology74/ce5.htm; and “Granada (Amache) Relocation Center Colorado,” in Report to the President: Japanese-American Internment Sites Preservation (US Department of the Interior, 2001), https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/internment/reporta3.htm. ↩︎

-

See “Going for Broke: The 100th Infantry Battalion,” National WWII Museum, August 1, 2020, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/japanese-american-100th-infantry-battalion. ↩︎

-

See “Name by Name Accounting Roster of Evacuees for Closing of Granada Camp” (War Relocation Authority, December 31, 1944), 172, https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/176117?ln=en; and an interactive Amache Camp Directory created by the University of Denver, https://www.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=38d3dc5b459d46bfae00576afb66af4f&extent=-11393355.7689%2C4585333.2233%2C-11389113.5138%2C4587509.29%2C102100. ↩︎

-

See Chang, ed., Asian American Art, 401. ↩︎

-

See “Going for Broke: The 442nd Regimental Combat Team,” National WWII Museum website, September 24, 2020, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/442nd-regimental-combat-team. ↩︎

-

See “Going for Broke: The 100th Infantry Battalion.” ↩︎

-

See “Timeline," Japanese American Museum of Art. ↩︎

-

“Granada (Amache) Relocation Center Colorado.” ↩︎

-

See a photograph of the painting by Pat Coffee, with typed notes on verso, War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement 1942–45, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/109977?ln=en#?xywh=-25%2C0%2C1548%2C1119&cv=. ↩︎

-

See James G. Lindley, “The Granada Relocation Center: A Narrative Report,” November 15, 1945, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records 1930–1974, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/175087?ln=en. ↩︎

-

See Alien’s Travel Permit, "Granada Relocation Center (Amache, Colorado) Forms and Permits, 1942–1945, Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-2. ↩︎

-

See “Name by Name Accounting Roster of Evacuees for Closing of Granada Camp.” ↩︎

-

See Application for Alien Enemy to Travel, "Granada Relocation Center (Amache, Colorado) Forms and Permits, 1942–1945, Tokio Ueyama papers, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-2. ↩︎

-

See Robert Harvey, Amache: The Story of Japanese Internment in Colorado during World War II (Scottsdale, AZ: Hawes & Jenkins, 2023), 282; and Lindley, “The Granada Relocation Center: A Narrative Report.” ↩︎

-

See “Japanese Artists Show Relocation Center Art,” Los Angeles Times, May 4, 1947. ↩︎

-

See the Bunkado website, accessed November 28, 2023, https://www.bunkadoonline.com/pages/new. ↩︎

-

See catalog in Collection of Bunkado, Inc.; and Mary Oyama, “Reveille,” May 2, 1947, clipping in scrapbook, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

See catalog in Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

See catalog in Collection of Bunkado, Inc.; and undated clipping, “Attn: Nisei artists,” scrapbook, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

See catalog in Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎