Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, drew the United States into World War II. Wartime hysteria, compounded by preexisting “racial discrimination, economic greed, and . . . unfounded fear,” ultimately led to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order No. 9066, signed on February 19, 1942, which “authorized federal troops to exclude anyone from any location as deemed necessary for national security.”1 While not explicitly stated, the order was aimed at people of Japanese descent, immigrants and citizens alike, living in western states. Soon, they would be forced from their homes. Most complied with imposed restrictions, which included curfews, travel restrictions, and frozen bank accounts, and ultimately with forced relocation, hoping that in a time of intense patriotism such submission would signal their loyalty.2

On March 18, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9102 establishing the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to formulate a program for Japanese American removal. Soon, evacuation notices appeared in public spaces, and community members began moving into “reception centers,” or temporary detention centers, where they would be held until removed to facilities further inland. They took only what they could carry.3

The Ueyamas were first detained at the Santa Anita Assembly Center, a racetrack converted into a holding center that, at its peak, held 19,000 people.4 At Santa Anita, barbed wire capped eight-foot fences around the perimeter, with search lights and armed guards placed at regular intervals. Tokio Ueyama’s painting The Evacuee (cat. 19, illustrated nearby) shows Suye inside one of the wood and tar paper barracks. Other evacuees lived in converted horse stalls. Hot, fly-ridden mess halls served thousands at a time. Privacy was nearly nonexistent. In the cramped barracks, many walls did not extend all the way to the ceiling. Toilet facilities were open rooms with boards with holes about a foot apart, like massive communal outhouses. Showers, too, were communal.5

In September, the Ueyamas were put on a train to Amache, an experience remembered by other evacuees as hot, long, monotonous, and uncomfortable.6 Upon arriving, the camp was not yet finished, much of the water was non-potable, and electricity was frequently unavailable.7 Once complete, the entire site encompassed more than 10,000 acres, the majority of which was devoted to agricultural production. The camp consisted of twenty-nine blocks of barracks, and apartments within measured between sixteen-by-twenty feet and twenty-four-by-twenty feet (fig. 1). Each apartment included cots, one light bulb, and a pad or blanket.8 Those incarcerated had to source or create all other necessities. Many fashioned beautiful gardens and planted trees to enhance their bleak living conditions.9 Each block included a recreation hall, mess hall, and lavatory. In addition to agricultural jobs, people also worked in the Amache Silk Screen Shop, the mess halls, the hospital, the newspaper the Granada Pioneer, the co-op store, and the local schools. Sports, dances, religious services, movies, clubs, and extracurricular classes, among other activities, helped alleviate boredom.10 Those forced to live at Amache worked to create a sense of normalcy and community even while battered by extreme temperatures and wind, surrounded by barbed wire fences, and shadowed by eight armed towers (fig. 2).

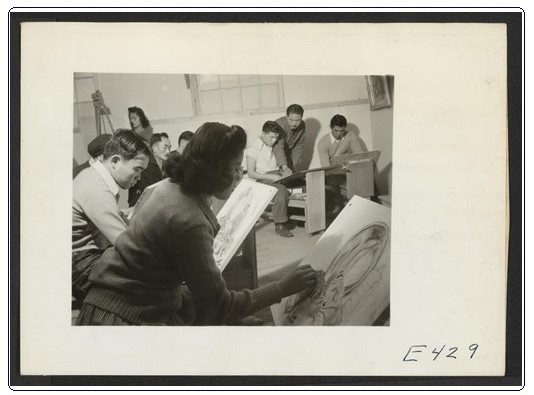

Ueyama’s relocation to Amache ruptured his previously rigorous exhibition schedule and the dynamic artistic community he and other Japanese American creatives had forged in Little Tokyo. It did not, however, stop him from painting. As part of the adult education program, he supervised and taught art classes three times a day, three days a week, with Koichi Nomiyama (1900–1984) and other instructors in the 7E block recreation hall.11 In a later interview, he stated that he “taught a painting class of 150 adults at Amache . . . Many people who had always wanted to try their hand at painting found their first opportunity there.”12

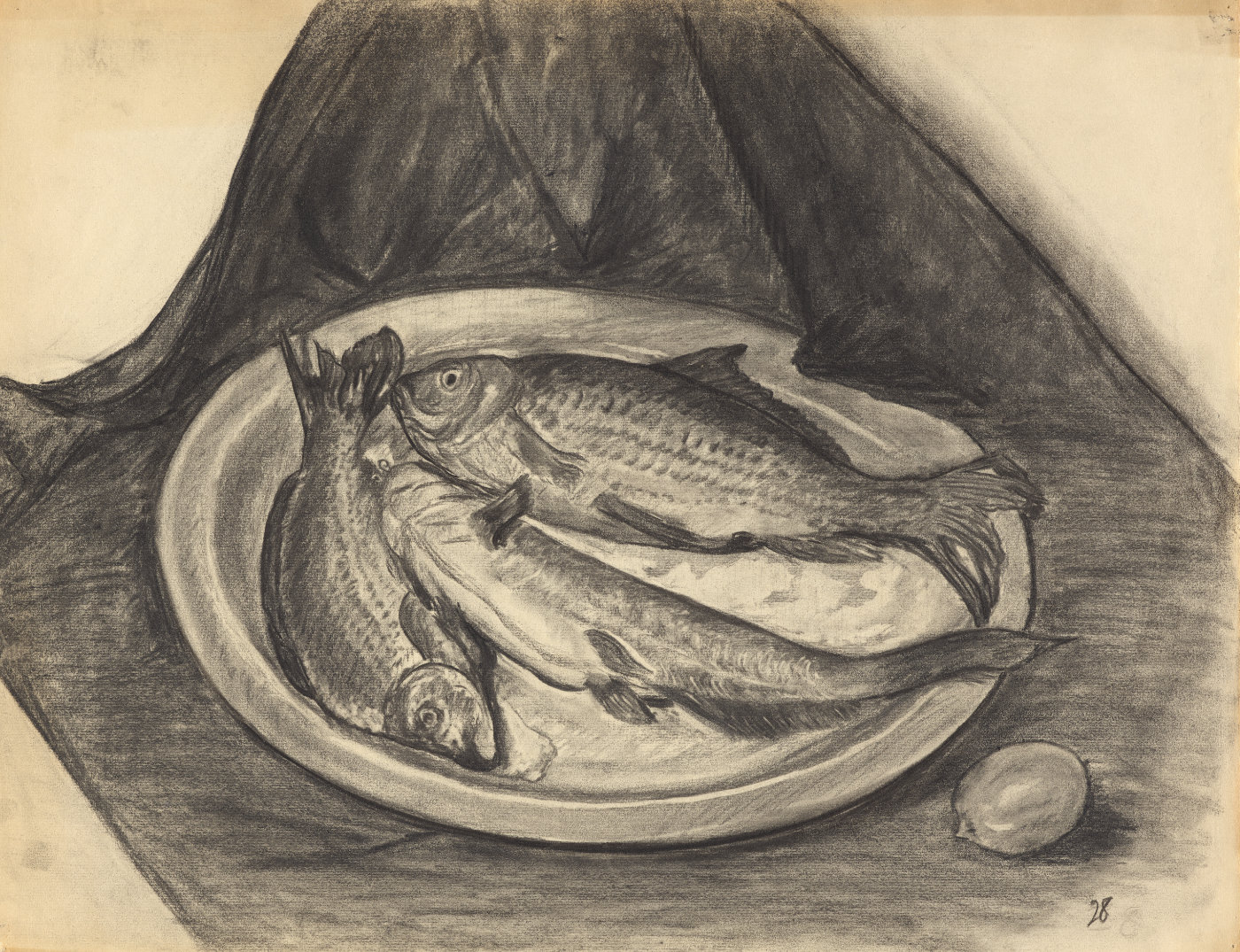

The artworks Ueyama and his students produced demonstrate that

they worked from what they had at hand, such as household

items (fig. 3). One of his charcoal

still lifes

features a bowl, vase, tea kettle, and citrus fruits, while

still lifes

features a bowl, vase, tea kettle, and citrus fruits, while

another

presents a platter of fish. In a

another

presents a platter of fish. In a

still life painted in February 1943, Ueyama depicts a large squash, dried corn cobs, and an oil

lamp on a table. A large sombrero hangs on the wall flanked by

a blue and red plaid fabric. The vegetables refer to the many

crops that those at Amache helped grow, both as part of the

camp’s work program as well as in their own victory

gardens.13

As ShiPu Wang writes in

his essay in this publication and

elsewhere, the sombrero may also allude to Ueyama’s time in

Mexico.14

In another oil from August 1943, Ueyama painted large

sunflowers in bloom, with a grasshopper perched on a leaf just

above his signature (cat. 27, illustrated below). Rather than

pulled around a stretcher or strainer, this oil on canvas is

cropped to the image and taped onto a thick compressed board,

a technique that Ueyama replicated in other works. It is

possible the board is the same material as had been used to

build the Amache barracks.15

He made use of what was available and may have approached his

challenging situation with shikata ga nai, or “it

can’t be helped,” and by practicing gaman, or

“accepting what is with patience and dignity.”16

still life painted in February 1943, Ueyama depicts a large squash, dried corn cobs, and an oil

lamp on a table. A large sombrero hangs on the wall flanked by

a blue and red plaid fabric. The vegetables refer to the many

crops that those at Amache helped grow, both as part of the

camp’s work program as well as in their own victory

gardens.13

As ShiPu Wang writes in

his essay in this publication and

elsewhere, the sombrero may also allude to Ueyama’s time in

Mexico.14

In another oil from August 1943, Ueyama painted large

sunflowers in bloom, with a grasshopper perched on a leaf just

above his signature (cat. 27, illustrated below). Rather than

pulled around a stretcher or strainer, this oil on canvas is

cropped to the image and taped onto a thick compressed board,

a technique that Ueyama replicated in other works. It is

possible the board is the same material as had been used to

build the Amache barracks.15

He made use of what was available and may have approached his

challenging situation with shikata ga nai, or “it

can’t be helped,” and by practicing gaman, or

“accepting what is with patience and dignity.”16

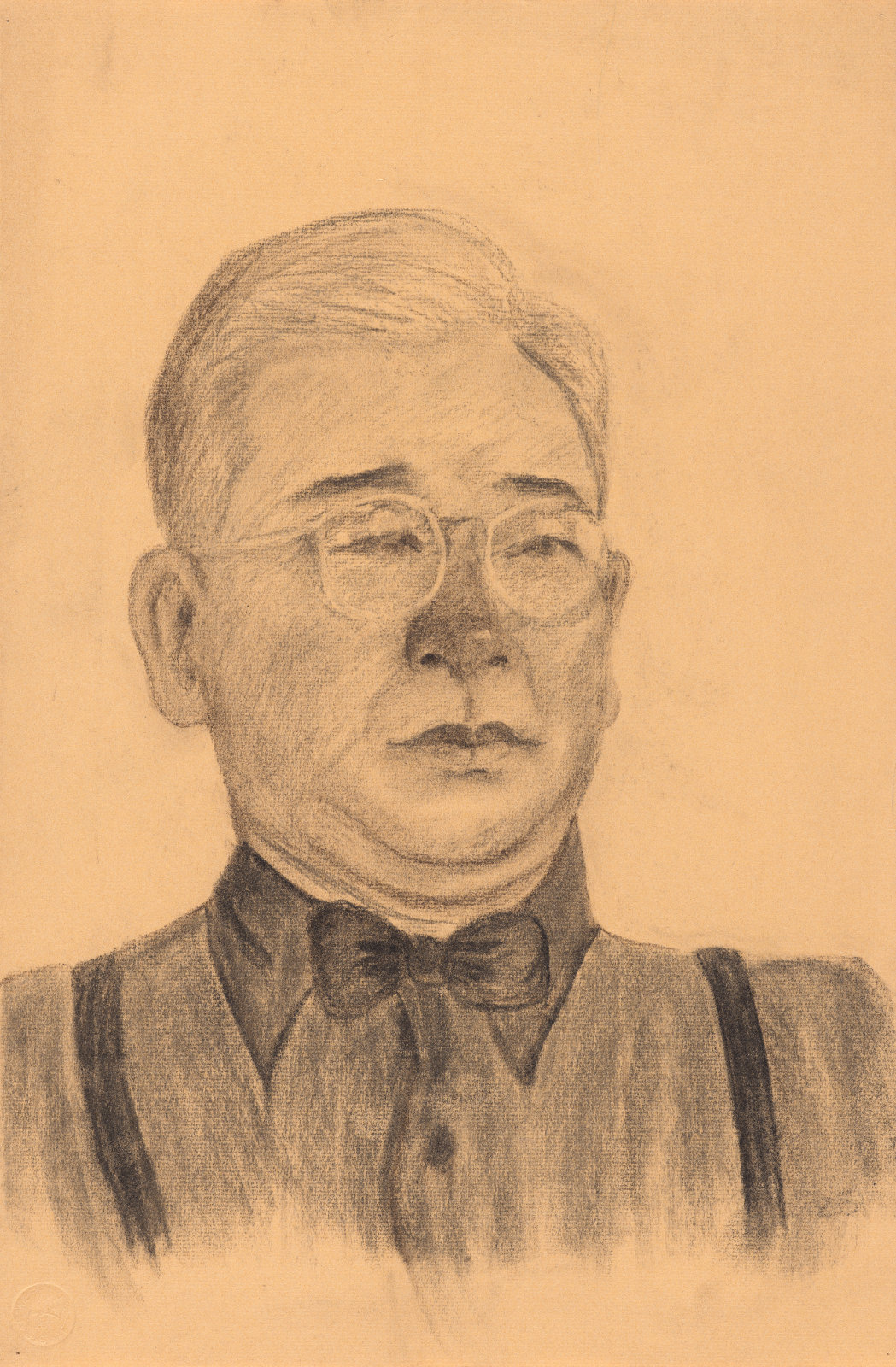

Portraits created by Ueyama and his students, such as charcoal

portraits of a

girl

and of a

girl

and of a

man with glasses, show that classmates and community members took turns

posing.17

His

man with glasses, show that classmates and community members took turns

posing.17

His

portrait of Tomoye Sawa

(known professionally as Gakuhajo) shows the musician holding

a biwa, or short-necked lute. In a vibrant oil

portrait, Ueyama painted a woman wearing a plaid top and red

lipstick (cat. 25, illustrated nearby). He sketched the

portrait of Tomoye Sawa

(known professionally as Gakuhajo) shows the musician holding

a biwa, or short-necked lute. In a vibrant oil

portrait, Ueyama painted a woman wearing a plaid top and red

lipstick (cat. 25, illustrated nearby). He sketched the

portrait of a stern soldier

on February 12, 1943, shortly after President Roosevelt

activated the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a segregated

Japanese American unit that would ultimately join the

segregated 100th Infantry Battalion formed in 1942. Thirty-one

members of Amache would be killed at war.18

portrait of a stern soldier

on February 12, 1943, shortly after President Roosevelt

activated the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a segregated

Japanese American unit that would ultimately join the

segregated 100th Infantry Battalion formed in 1942. Thirty-one

members of Amache would be killed at war.18

Landscapes populate Ueyama’s Amache oeuvre.

One oil

captures the dry plains landscape with barracks in the

background, while another features a closer look at life in

the camp, complete with basketball hoop made from found

materials, transplanted trees, laundry on a line, and figures

in jeans and T-shirts (cat. 29, illustrated nearby).19

The organic arcs of dried cornstalks in the foreground,

probably part of a victory garden, echo the rounded billow of

clouds above.

One oil

captures the dry plains landscape with barracks in the

background, while another features a closer look at life in

the camp, complete with basketball hoop made from found

materials, transplanted trees, laundry on a line, and figures

in jeans and T-shirts (cat. 29, illustrated nearby).19

The organic arcs of dried cornstalks in the foreground,

probably part of a victory garden, echo the rounded billow of

clouds above.

One of Ueyama’s pastels

shows dark clouds above barracks, fence, and water tower

(which still stands today), while

One of Ueyama’s pastels

shows dark clouds above barracks, fence, and water tower

(which still stands today), while

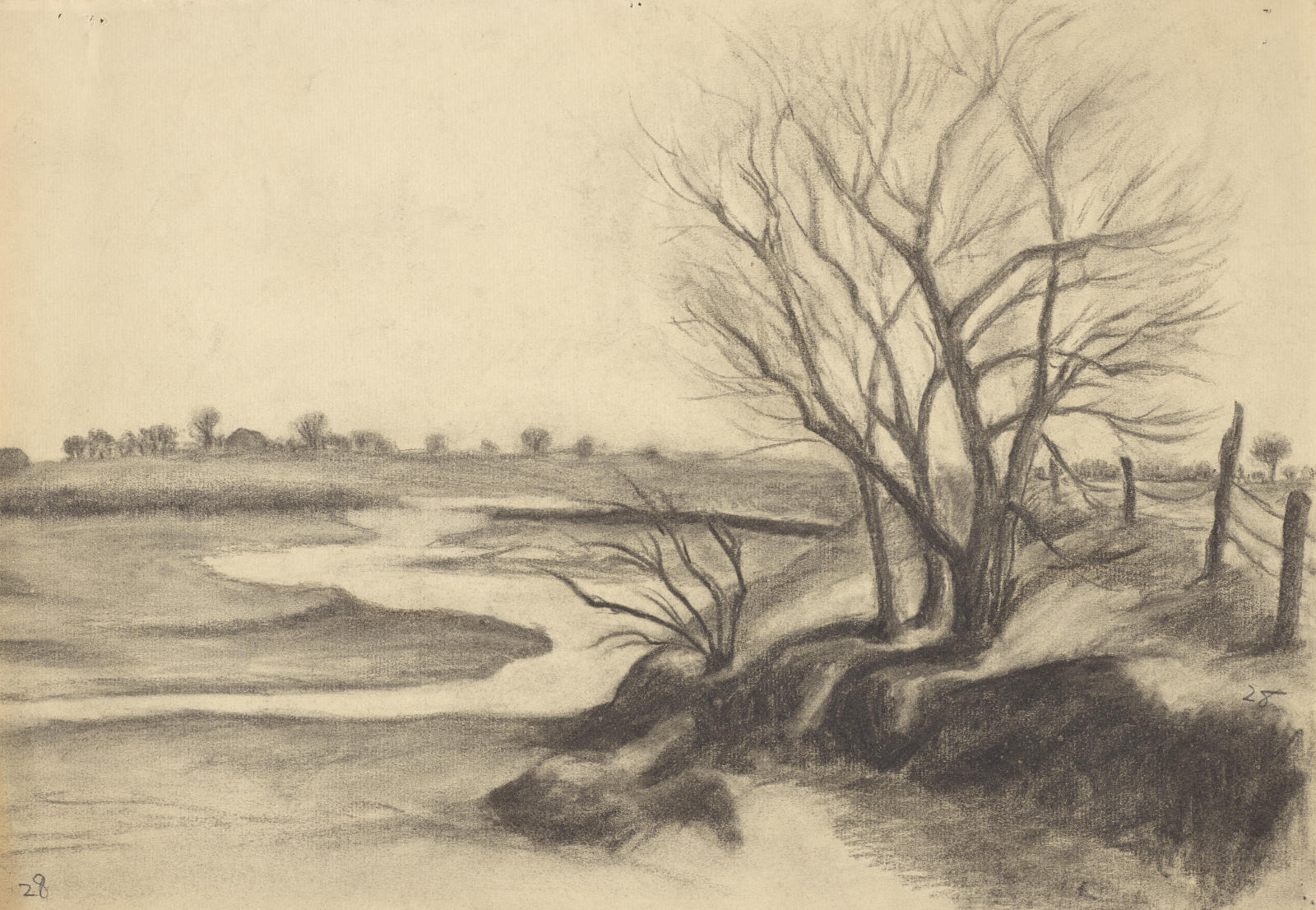

a brighter composition

shows people working in a field, the Amache barracks in the

background. In other landscapes, Ueyama depicted scenes

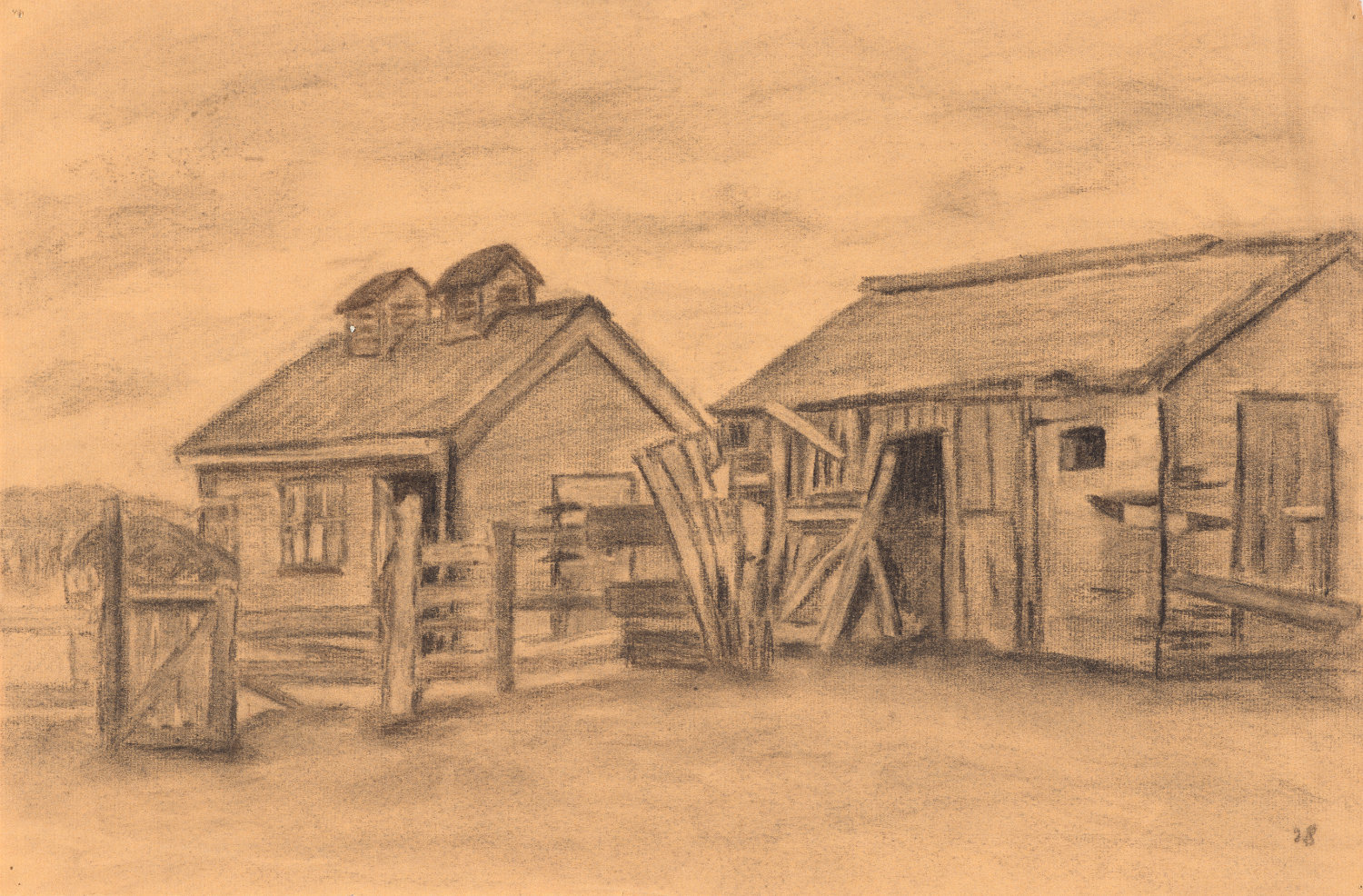

outside the camp. Two charcoal drawings feature

a brighter composition

shows people working in a field, the Amache barracks in the

background. In other landscapes, Ueyama depicted scenes

outside the camp. Two charcoal drawings feature

wintertime trees

and fences, while two others present Granada houses and

wintertime trees

and fences, while two others present Granada houses and

outbuildings.

outbuildings.

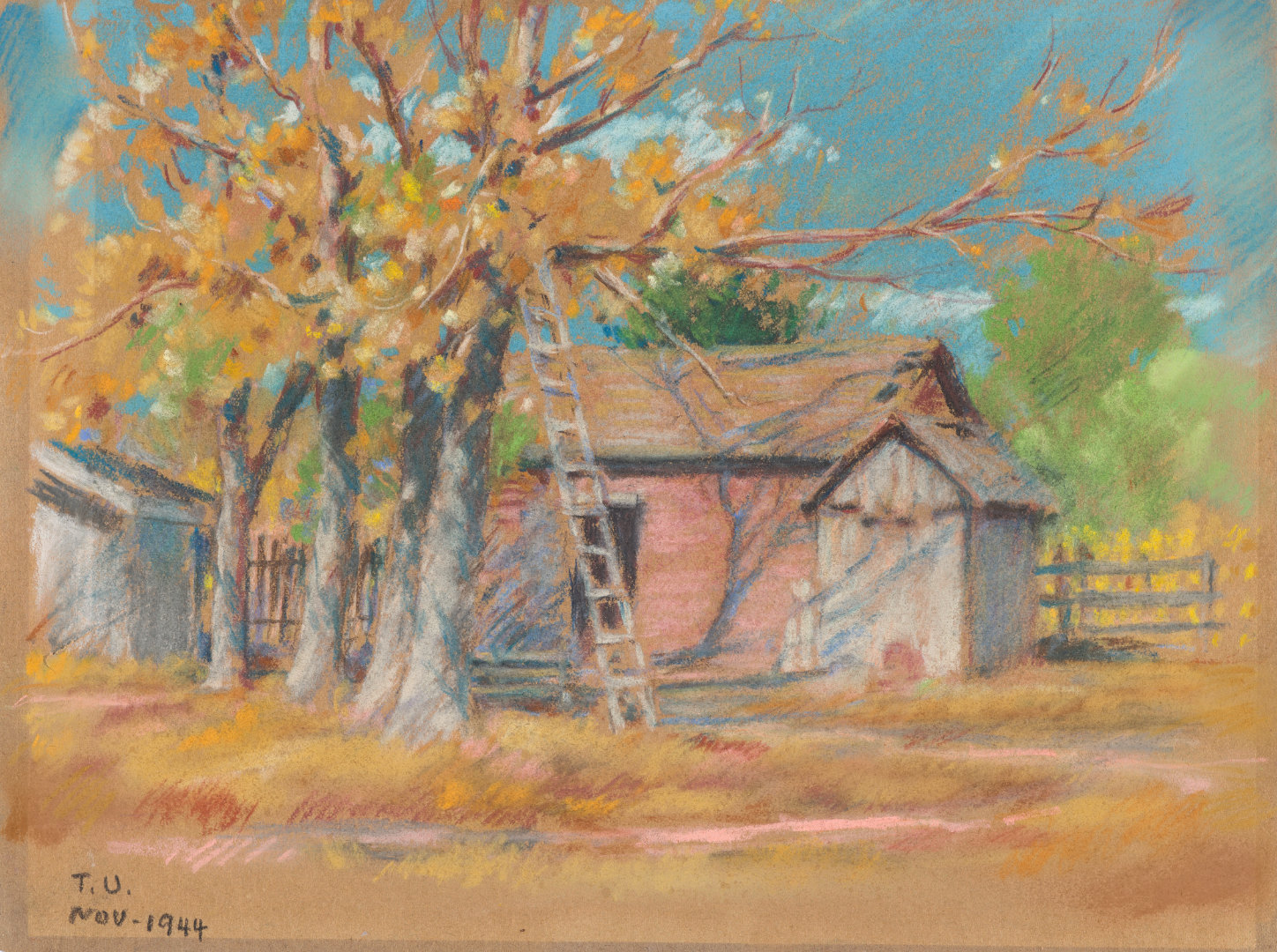

One oil

shows a bony horse standing in the sun by a faded red barn and

part of an antique hitch wagon. Other barns bathed in warm

light show up in

One oil

shows a bony horse standing in the sun by a faded red barn and

part of an antique hitch wagon. Other barns bathed in warm

light show up in

two

two

pastels. A

pastels. A

winter landscape, also taped to fiber board, presents a scene of red willows

glowing against snow. Ueyama’s landscapes—which seem to

celebrate the land, sky, and rural architecture of

Granada—rarely allude to the harsh conditions of his forced

confinement. In his essay for this publication, Wang provides

a deeper dive into some of Ueyama’s wartime work and places it

in the context of artworks by other Japanese Americans

incarcerated during the war.

winter landscape, also taped to fiber board, presents a scene of red willows

glowing against snow. Ueyama’s landscapes—which seem to

celebrate the land, sky, and rural architecture of

Granada—rarely allude to the harsh conditions of his forced

confinement. In his essay for this publication, Wang provides

a deeper dive into some of Ueyama’s wartime work and places it

in the context of artworks by other Japanese Americans

incarcerated during the war.

Ueyama’s landscapes indicate that he, like many Amacheans, circulated within Amache’s 10,000 acres as well as beyond its fences. Some of the barns in Ueyama’s landscapes may be part of the infrastructure of the historic XY Ranch, founded by Fred Harvey in 1889 and utilized for Amache’s agricultural enterprise (fig. 4).20 Other structures, as well as some of the river drainages, may be scenes from the town of Granada and its environs. Many Amache residents worked outside the camp, and permits could be obtained to travel further. Similarly, residents of the greater region visited Amache for work, shopping, and social and cultural opportunities. At this time, Amache was the largest “city” in the region, with its own schools, sports leagues, Boy Scout troop, theatrical and musical performances, and art exhibitions, including the 1943 Arts and Crafts Festival in which Ueyama exhibited The Evacuee (cat. 19, illustrated above). Camp boundaries were controlled but porous.21

A set of fifteen stones hand-polished by Ueyama while incarcerated reinforces this fact (cat. 42, illustrated nearby). They are not native to the Granada area, which is composed of sand and limestone, yet they found their way to Amache—perhaps picked up in the drainage of the Arkansas River, sent to Ueyama by friends elsewhere, or selected on travels further afield.22 While their full stories remain unknown, their existence alludes to circulation beyond camp fences.

Polishing these stones released their humble beauty and may have helped Ueyama endure the passage of time. Earlier, when traveling in Europe, he left a reflective note in his journal:

the stone on the road side

begins its history of existence

only when it is kicked or turned.

Over twenty years later, when polishing these stones, Ueyama provided each a history of existence. The stones beg to be held, turned over, and engaged with. In a quiet way, they signal agency (in the choice of stone and in polishing it) and relationality (by unlocking the inner beauty of each stone and, possibly, through a network of people who may have helped source them). They are a reminder that existence is marked through interaction with others and that nurturing beauty plays a central role in creating and sustaining such interactions.

-

Robert Harvey, Amache: The Story of Japanese Internment in Colorado during World War II (Scottsdale, AZ: Hawes & Jenkins, 2023), 30. ↩︎

-

Around 9,000 people voluntarily relocated inland. See ibid., 37 and 41. ↩︎

-

According to evacuation notices, the belongings they carried had to include bedding and linens, toilet articles, extra clothing, plates and silverware, and essential personal effects. See Robert Y. Fuchigami, Amache Remembered: An American Concentration Camp, 1942–1945 (Parker, CO: BookCrafters, 2020), 15. On March 1 and April 30, 1942, Ueyama made inventory lists of the couple’s belongings in a small black notebook. The sixty-six boxes plus larger items would remain indefinitely with Mr. and Mrs. Wilson in Los Angeles. See small black notebook, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. I am grateful to Noriko Okada for reviewing the lists, much of which is in Japanese, and confirming their contents. ↩︎

-

Harvey, Amache, 54. ↩︎

-

For further description, ibid., 53–55. ↩︎

-

Window shades had to be kept drawn. Trains traveled a variety of routes that usually took about three days and three nights to complete. Stops were short and infrequent, if provided at all. See ibid., 100–03. The first arrivals to Amache on August 27, 1942, were from the Merced Assembly Center. They helped to complete construction on the as-yet-unfinished camp. Eight more trains from Merced arrived between September 3 and 18. Six trains from Santa Anita arrived between September 19 and 30. By the end of September, 7,567 Japanese people had arrived at Granada. See ibid., 104–06. ↩︎

-

See ibid., 108–09. ↩︎

-

“Amache Construction,” Amache.org, accessed November 29, 2023, https://amache.org/amache-construction/. For maps, see “Maps,” Amache.org, accessed November 29, 2023, https://amache.org/map/. ↩︎

-

For resources on Amache gardens, see the University of Denver Amache Research Project, last updated February 22, 2023, https://portfolio.du.edu/amache. ↩︎

-

To browse issues of the Granada Pioneer, 1942–45, see the Library of Congress digitized archives, https://www.loc.gov/item/sn83025522/?st=calendar. ↩︎

-

See Gordon Chang, Asian American Art: A History, 1850–1970 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008), 401. ↩︎

-

“Japanese Artists Show Relocation Center Art,” Los Angeles Times, May 4, 1947. ↩︎

-

The objective of the agricultural project at Amache was to grow adequate produce for Amacheans. The project was so successful that produce was sometimes sent to other camps. See Fuchigami, Amache Remembered, 49; and Harvey, Amache, 169–70. ↩︎

-

The sombrero takes on increased poignancy “as an image that recalls a happier time—and certainly a freer time.” ShiPu Wang, Chiura Obata: An American Modern (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2018), 38. ↩︎

-

Regarding the construction of Amache, see “Amache Construction,” https://amache.org/amache-construction/. ↩︎

-

See Delphine Hirasuna, The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps, 1942–1946 (Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press, 2005), 7; and Harvey, Amache, 57. Family member David Hirai, who knew Ueyama, remembered that, when asked about the camp, Ueyama did not want to talk about it and said that they had made the best of it. Conversation with the author, April 2024. ↩︎

-

Black-and-white photographs of Ueyama’s Amache portraits show that a variety of sitters, both Japanese and Caucasian, sat for him and, presumably, his classes. See red scrapbook, Collection of Bunkado, Inc. ↩︎

-

“Granada (Amache) Relocation Center Colorado,” in Report to the President: Japanese-American Internment Sites Preservation (US Department of the Interior, 2001), https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/internment/reporta3.htm. ↩︎

-

Regarding the trees, see “Amache Construction,” https://amache.org/amache-construction/. ↩︎

-

J. Burton, M. Farrell, F. Lord, and R. Lord, “Granada Relocation Center,” in Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites (Tuscon, AZ: Western Archeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, 2000), https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anthropology74/ce5.htm. ↩︎

-

I am grateful to Bonnie Clark, professor of archaeology at the University of Denver and leader of the DU Amache Project, for her insight about Amache’s porous boundaries. Conversation with the author, November 29, 2023. ↩︎

-

Thanks to Clark for talking through these stones and explaining the geology of the Granada area. Conversation with the author, November 29, 2023. ↩︎