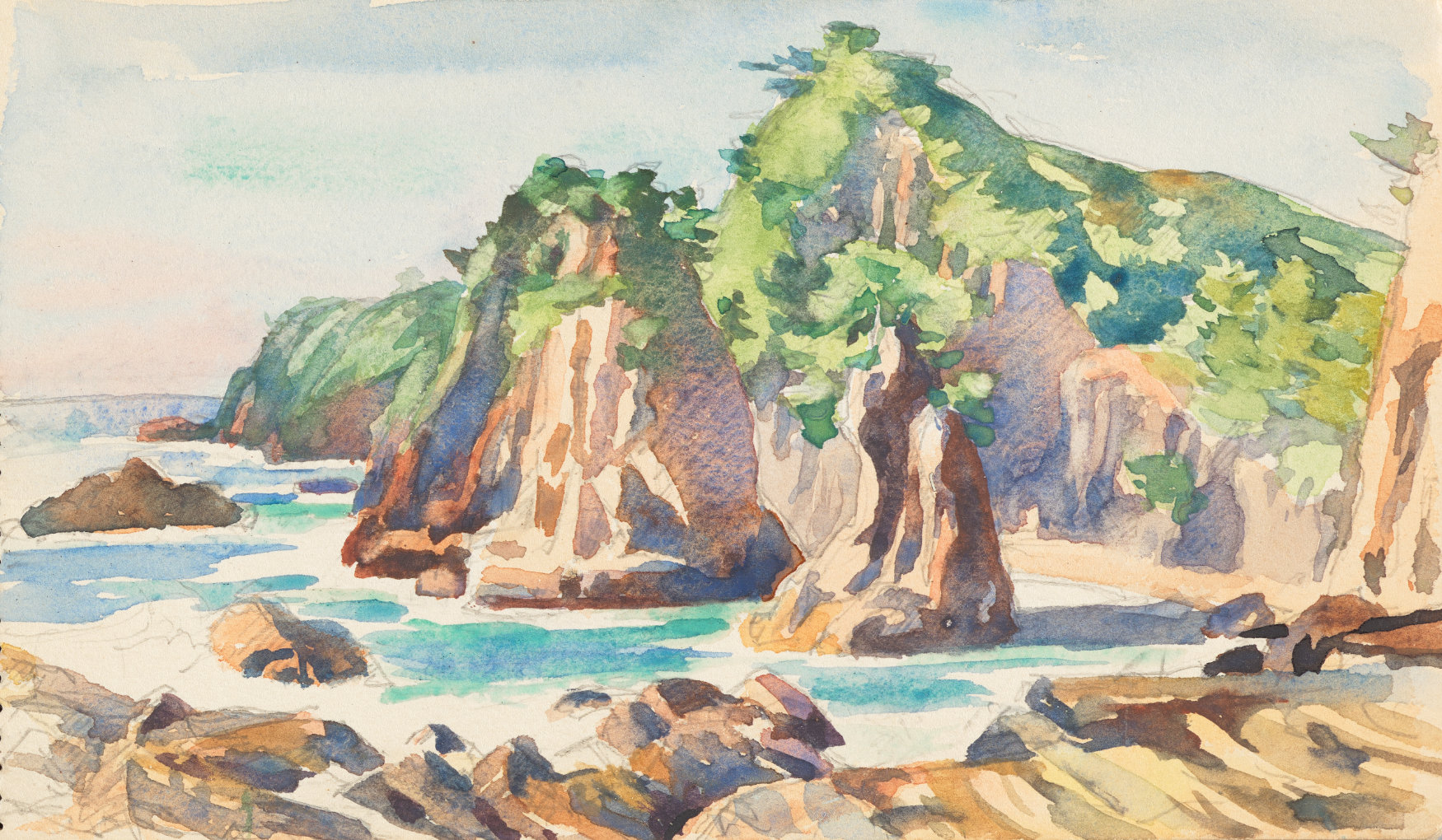

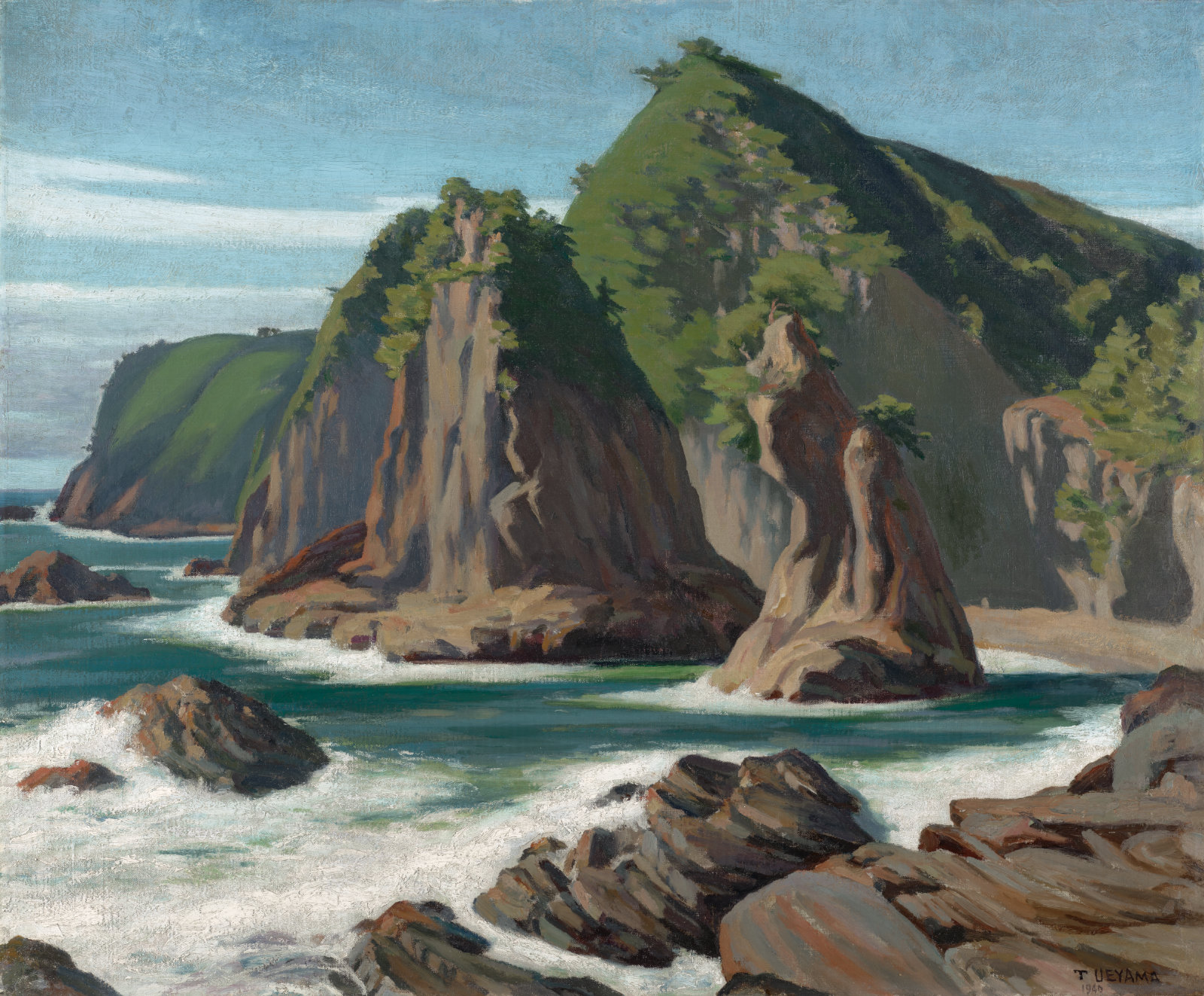

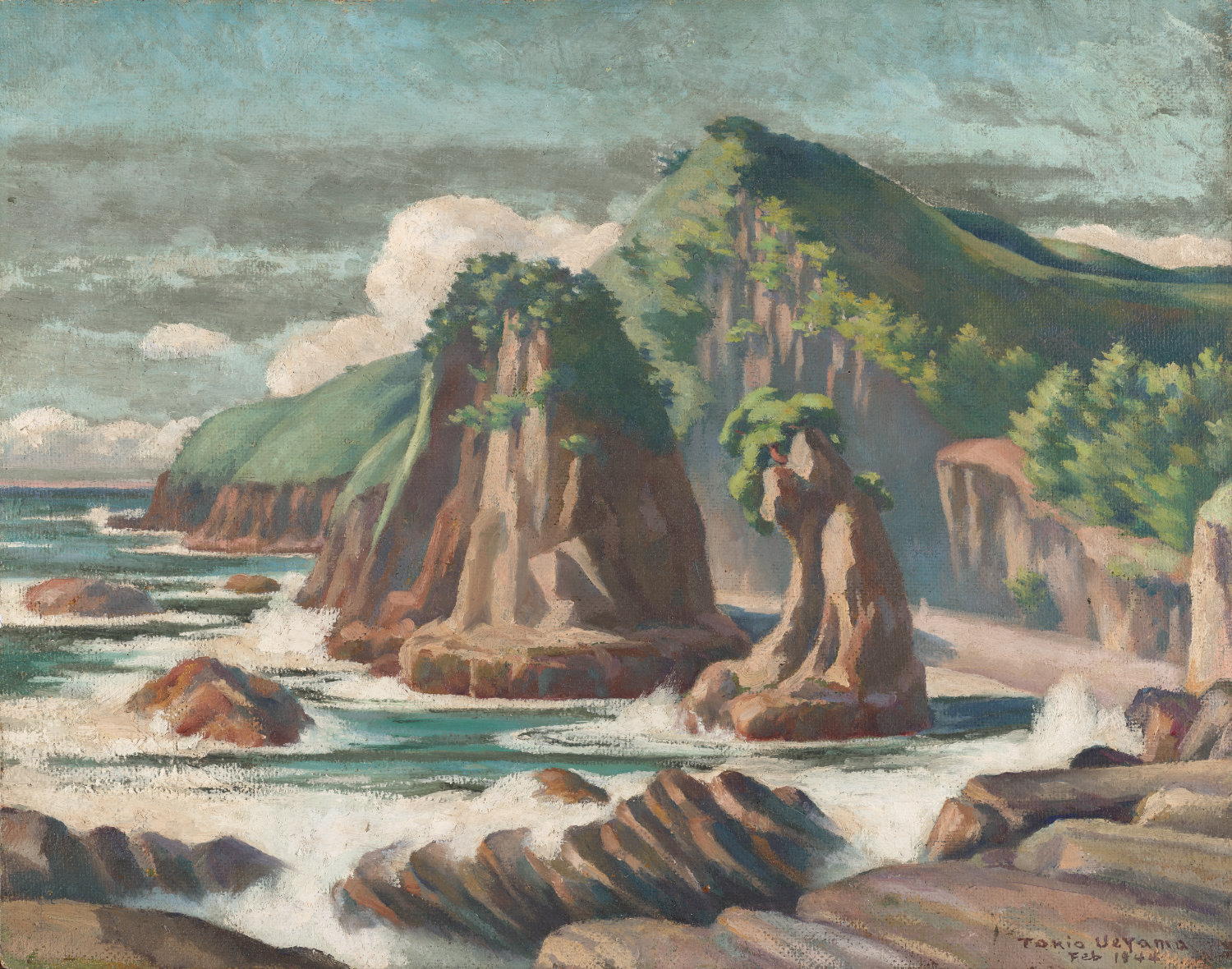

When I first encountered several paintings of a similar coastal scene by Tokio Ueyama, I admittedly did not regard them as something particularly special. Sure, seeing multiple versions of the same rock formations across a watercolor sketchbook, a small oil, and a larger finished oil painting did generate a mental note: this must be a meaningful place for the artist. I later learned a few factors that made this series of landscapes stand out even more from the hundreds of artworks I have seen by this artist: the smaller oil, dated February 1944, was created at the Amache incarceration camp where Ueyama was imprisoned during World War II, and the scenery features the coast of Katsuura (勝浦), a part of Nachikatsuura (那智勝浦) in the southeast part of Wakayama Prefecture (和歌山県) in Japan, the same prefecture where Ueyama was born and raised.1

The Katsuura series was produced over a span of nearly eight years. Ueyama likely made the watercolor sketch in 1936–37, during his only return to his hometown in Wakayama since immigrating to the United States in 1908. He worked on at least one smaller oil sketch (4½ × 10 inches) probably in preparation for the much larger painting (38 × 43½ inches). We know he began working on this larger painting on February 4, 1940, thanks to the short entries of his daily activities that he wrote in multiple daybooks over many years; the last mention of Katsuura was on February 26, 1940.2 Two final Katsuura landscapes, one in oil and one in charcoal, were created when Ueyama was incarcerated in Amache from 1942 to 1945.

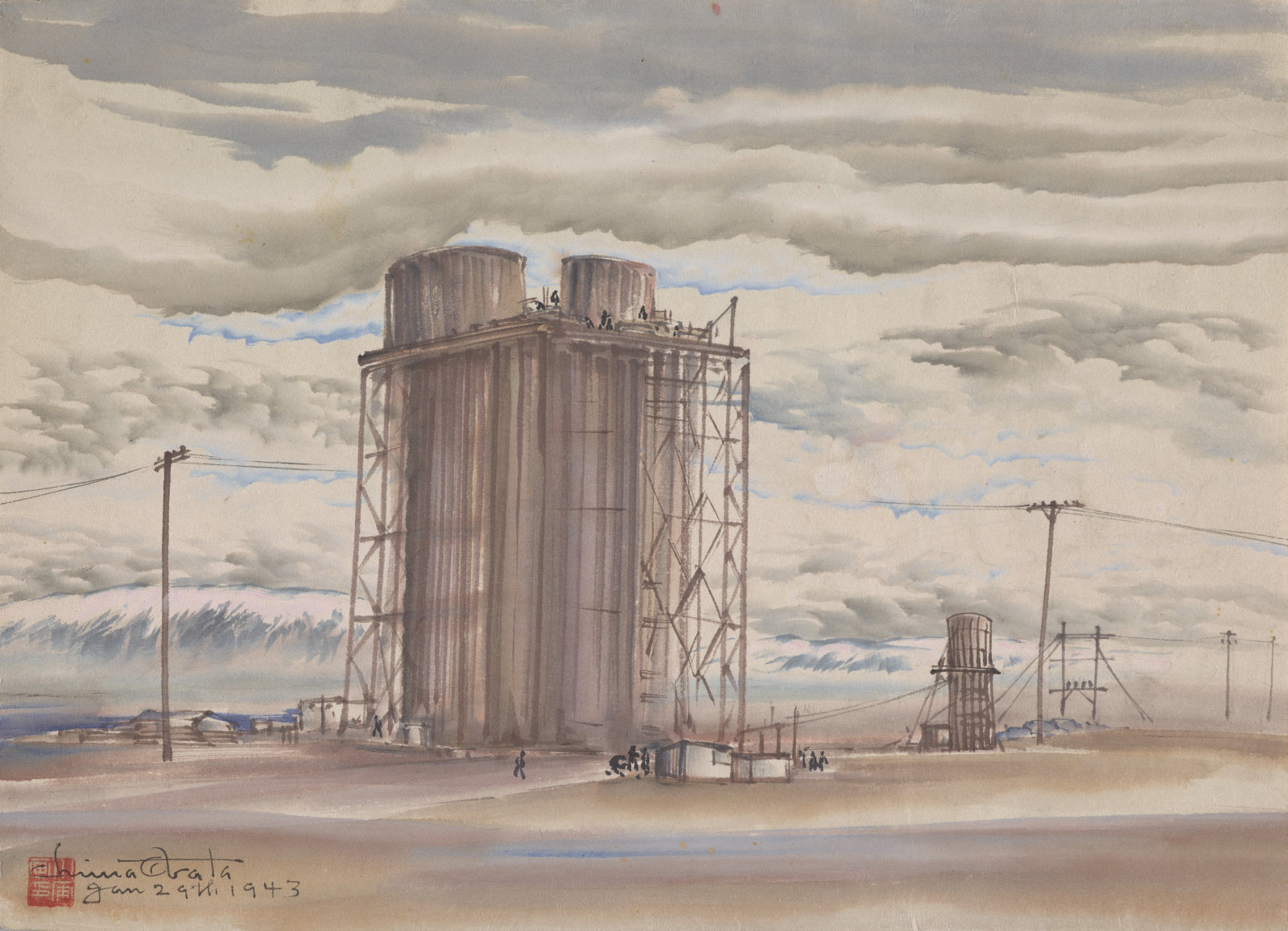

Ueyama did not leave any explanations for why he decided to create a 1944 version of the Katsuura coast; his extant diary entries end in 1941. But it would be reasonable to consider Ueyama’s painterly “revisit” to his hometown to be motivated by homesickness or nostalgia, especially when his physical freedom and any possibility of seeing Japan again were taken away without a foreseeable end. Recalling and re-creating the open and lush seaside with his brush when he was confined to Amache in the arid and isolating High Plains of Colorado provided some creative alternatives to, and perhaps relief from, depicting a desolate environment with barracks, dust, and storms (fig. 1). And the Katsuura landscape may have served as a kind of demonstration and visual stimulus to the art classes that Ueyama taught at the camp, as those instructions usually centered around portraiture, still life, found objects, and local scenes.

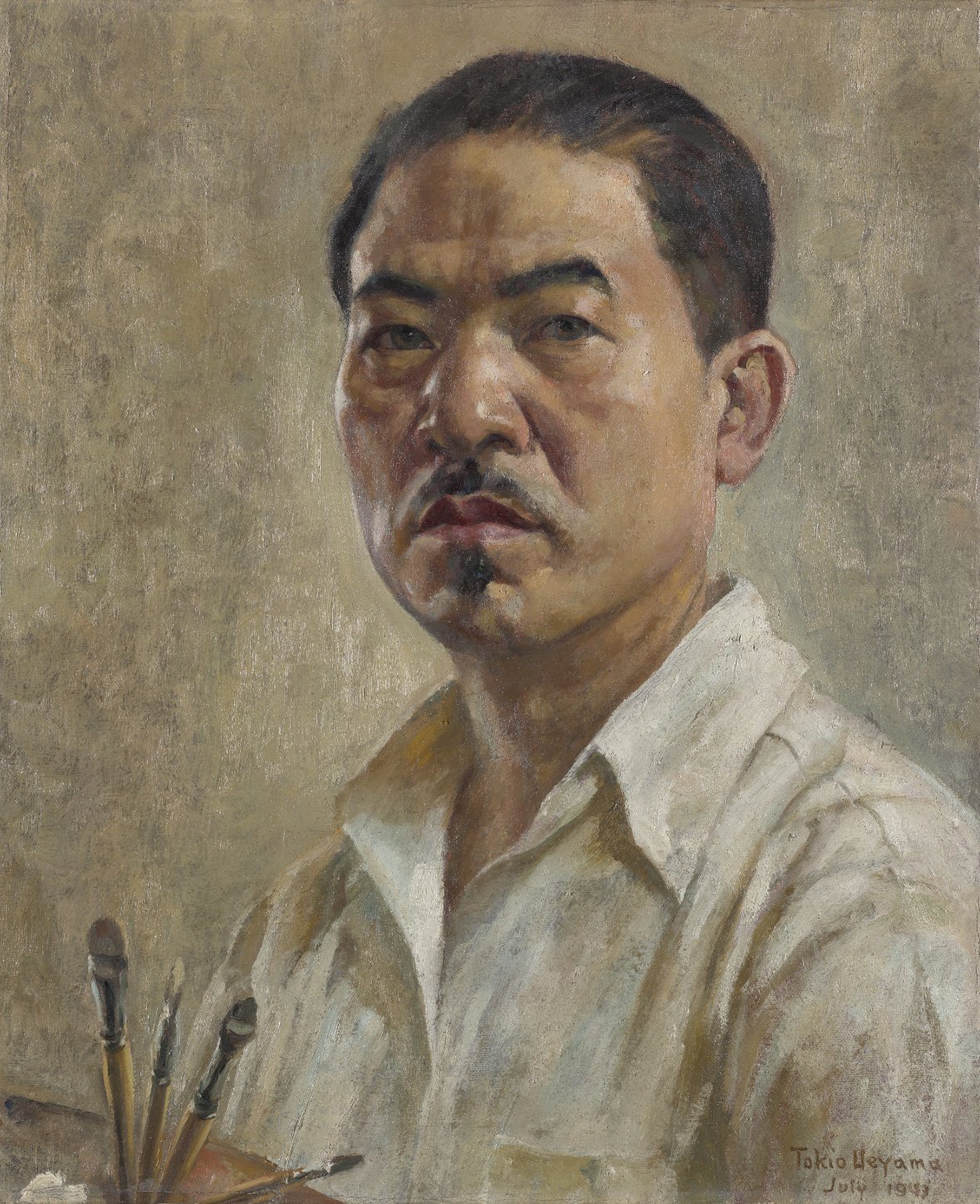

Ueyama indeed maintained high productivity even under

incarceration, as works in this exhibition can attest. Many of

his other camp paintings appear to be straightforward

depictions of people, things, and scenes, but they do allow

for deeper readings as well, especially in relation to his

prewar imagery. For instance, his Self-Portrait of

February 1943 is a dignified self-representation of a serious

artist, as the depicted accoutrements suggest (cat. 20,

illustrated below). The meticulous modeling of his fleshy

face, with touches of sheen and blotches of flush, complements

a contemplative and determined gaze. The simplicity of the

background is a contrast to that in his 1924 self-portrait,

where a nude statue fills the space—a signifier of his

artistic training in the European tradition at the

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (cat. 4, illustrated

below). The younger Ueyama is rendered in looser brushwork

with great vitality; the glistening eyes, equally piercing as

those in the 1943 self-portrait, project intensity and perhaps

an aspiring artist’s optimistic outlook toward his burgeoning

career. The Amache self-portrait, more subdued and somber in

tone, thus serves as a poignant reminder of the passage of

time (with nearly twenty years between the two) and

drastically changed circumstances. Similarly, Ueyama’s

untitled still life, painted in February 1943, offers a view of seemingly

ordinary objects. The inclusion of an eye-catching sombrero

adds texture and visual interest to the composition, but it

also evokes Ueyama’s Mexican sojourn of 1925, a bygone era

when he was free to roam the world—see

JR Henneman’s essay and the

timeline in this publication.

untitled still life, painted in February 1943, offers a view of seemingly

ordinary objects. The inclusion of an eye-catching sombrero

adds texture and visual interest to the composition, but it

also evokes Ueyama’s Mexican sojourn of 1925, a bygone era

when he was free to roam the world—see

JR Henneman’s essay and the

timeline in this publication.

Following this line of interpretation, we could read the 1944 Katsuura landscape as a poignant visual reference of Ueyama’s past journey to a meaningful place, which enabled him to “re-experience” that coastal spot. The process of painting the same scene, either from memory or an old sketch, would have required him to recall details and sensations of standing at that far-flung corner of his home prefecture as crashing waves splash against jutting rocks. Re-creating Katsuura visually became an exercise in nostalgia as well as escape, a momentary respite from the dusty desolation surrounding him at Amache. Yet, this recollection is a wistful simulation of a place to which he may never be able to return, at least as it must have seemed at that moment of being confined to inland Colorado. Conversely, the landscape can be regarded as an existential affirmation as well: that he was still alive and able to paint—that even though he may have lost his freedom and belongings, he still had his artistic skills and the memories that made up who he continued to be.

Ueyama’s 1944 Katsuura canvas brings up a rich array of critical considerations regarding landscape paintings created by Japanese Americans under wartime incarceration. Could Katsuura be considered a “camp painting,” even though its depiction is of a place in Japan that the artist re-created from memory? If so, it seems to expand our existing definitions of “camp art,” which have tended to emphasize or even valorize visible signifiers of displacement and confinement, as well as documentation and illustration of wartime trauma. Could we instead untether “camp imagery” from identifiable subject matter of incarceration and regard it as a broader and varied kind of visualization of experiential and internal processing, of existential negotiation and affirmation? That is: the act of artistically re-presenting one’s physical and subjective experiences, when one’s very existence is under threat, functioned as a vital means of making sense of the existential crises one’s going through. Ueyama and other incarcerated artists leveraged their creative tools to confront distressing situations, to maintain control, order, and normalcy (to the extent possible under imprisonment), and to temporarily “escape” from harsh realities. Camp landscapes offer revealing insights into incarcerated artists’ internal grappling with geographical, temporal, geopolitical, and emotional conflicts and dissonances. Beyond being subjective visualizations, such paintings also serve as important accounts that collectively contribute to the composition of a chapter of American history with which we continue to reckon.

Taking a broader view, we see that many of the diverse landscape paintings produced by incarcerated artists of Japanese descent are more than documentary in nature. While many do focus on the “now,” depicting that which surrounded and confined them as they lived through the unjust imprisonment one day—and one painting—at a time, their imagery functioned as a kind of “intervention” as the artists leveraged creative tools to represent, aestheticize, and transform their environment and experience. For example, Chiura Obata (1885–1975), Ueyama’s contemporary colleague and a San Francisco Bay Area artist renowned for his paintings of Yosemite and Sierra Nevada, produced numerous landscapes during his wartime confinement at the San Bruno Assembly Center in California and the Central Utah Relocation Center (Topaz).3 Many of his images captured the drastic fluctuations of weather and the heat, dust, and storms blanketing Topaz. But as I have analyzed elsewhere, Obata adopted an approach of picturing the camp from an elevated perspective, as if the artist were hovering above the ground or on a distant hill (even at nighttime). It is an imaginary position that implies a kind of psychological distancing—detachment as coping mechanism, perhaps—while the “all-seeing” view takes on a broader perspective that makes sense of the harsh reality and, in turn, affirms one’s place in it. Such a pictorial strategy produced images that are aesthetically pleasing while adding poignancy and ambivalence, as seen in Moonlight Over Topaz, Utah (1942; fig. 2), for example—a work that was commissioned by the Japanese American Citizens League and presented to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in 1943, who displayed the painting in her New York City apartment until her death.4

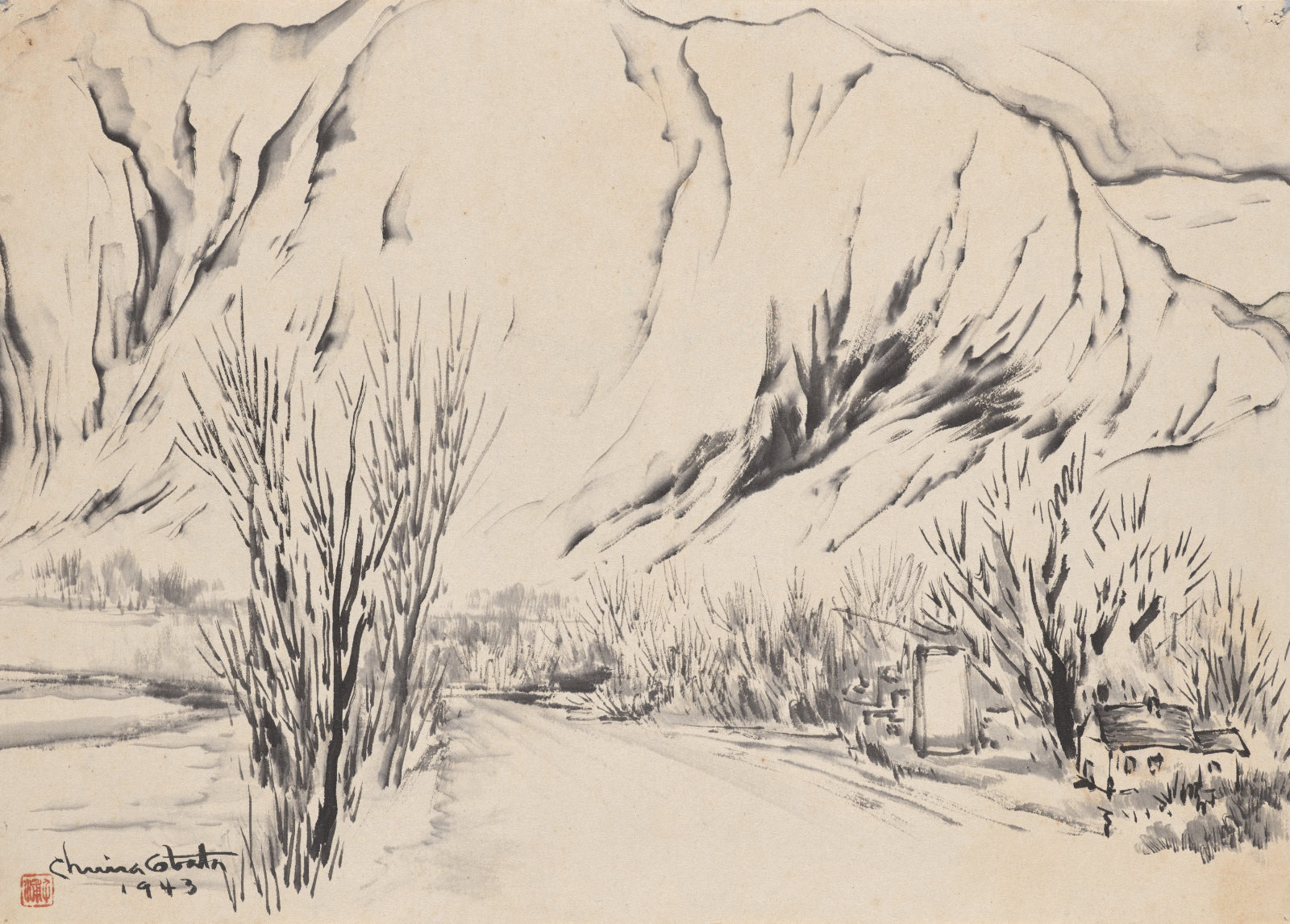

Such a painterly strategy of transforming barren and inhospitable surroundings into emotive visual expressions is evident in the Obata paintings that entered the Denver Art Museum’s collection in 2022. In Clouds Over Water Tower and Landscape Near Topaz, for instance, Obata applied his expert handling of sumi-e (Japanese ink and brush painting) to capture natural elements in fluid, energetic lines (figs. 3 and 4). Beyond the imposing water tower is a snow-capped mountain range that looks like roiling waves; some dark clouds dance above, allowing glimpses of a bright, blue sky. The monochromatic Landscape Near Topaz, likely painted on one of the excursions that the incarcerated people were allowed to take later during wartime, presents a mountain that seems to be breathing and expanding, as if it were about to devour or envelop the incoming traveler. The upward brushstrokes that render the trees and slopes guide the viewer’s attention skyward, beyond the forbidding mountain that blocks the view of and, by implication, access to a free world on the other side. While this ink landscape is reminiscent of Obata’s prewar imagery of “Great Nature” (Daishizen, in his native Japanese), the economy of his single-color brushwork adds to the visual representation of the bleak circumstances that surrounded the artist and his fellow camp prisoners.

The Amache landscapes by Ueyama in this exhibition demonstrate a similar impulse on the artist’s part to transform views of the arid and drab environment into imagery replete with aesthetic qualities that belie their traumatic context. He carefully (re)arranged structures, trees, bushes, and clouds, likely taking creative licenses on the actual scenes he observed to compose the fore-, middle, and background expected in a classic landscape painting. In the 1944 Untitled (Barracks with Pond), for instance, the pond and a lone shed serve as countervailing elements that anchor the flat land with rows of barracks in the distance (cat. 28, illustrated below). In Untitled (Amache Landscape with Barrack and Tower), dated April 1944, the two structures stand in the lower center of the composition, allowing Ueyama to render the grey clouds in crosshatching strokes that suggest morphing fluffiness gliding through an expansive sky (cat. 33, illustrated below). These, along with a few more Amache paintings in this exhibition, make up a group of imagery that could have been received as an artist’s celebration of the idyllic, rural beauty of the American Southwest. They are, but by an incarcerated artist whose freedom this country ripped away, adding dimensions of irony, poignancy, and historical gravitas.

The act of looking up and capturing nature’s stunning light is evident in other artists’ paintings. Hisako Hibi (1907–1991), an artist also incarcerated at Topaz and the wife of Obata’s good friend Matsusaburo George Hibi (1886–1947), used oil paint to create spectacular views of the sun’s radiant display. Her Eastern Sky 7:50 A.M. of February 25, 1945, and Western Sky, of Topaz, Utah, in July 1945, are expressionistic, almost abstract depictions of breathtaking views that the artist took care to capture (figs. 5 and 6). The contrasting colors of crimson against charcoal and yellow against persimmon, as well as free-flowing lines and organic forms in the sky versus heavier, dark lines on the ground, all contribute to an immersive, sensorially rich viewing experience. Hibi minimizes the people, barracks, and even mountains, relegating them to the lower part of the composition and instead highlighting the vastness of the open sky and the infinitesimal human existence.

The skyward view and the cloud motif in Hibi’s landscape paintings convey more than an appreciation of nature’s awesome beauty. In Floating Clouds (April 1944), for instance, she chose to let her eyes and imagination soar and play with the clouds as she depicted cotton candy–like fluffiness frolicking in the air above the barracks (fig. 7).5 The scene has a sense of serenity that belies the reality of the painter living in an inhospitable, challenging place while raising two young children and teaching and helping at the art school that her husband and Obata established at Topaz.

Hibi’s own commentary on the canvas’s back is revealing: “Topaz sky / It was an interesting cloudy day / Floating clouds / フワリ フワリ フワリ [fuwari, fuwari, fuwari] / Free, free, freeforme [sic] in the spacious sky / I want to be free, as free as that cloud I see up above Topaz.” Fuwari is a kind of onomatopoeia, meaning “flutter, fluffy, floating.” Hibi’s words thus add a descriptive, sonic dimension to her visual representation of what she saw as well as her thoughts and emotions: her desire to be free from the physical confinement and the grave injustice that she (and fellow Japanese Americans) experienced. The proclamation “I want to be free” was likely added to the painting’s verso later in her life (she revisited and wrote on the back of many paintings). But it serves as both an honest retrospection on the artist’s state of mind under incarceration and a statement of hope and self-motivation that led her on a decades-long journey, through wartime and postwar challenges, to pursue her own voice and freedom in both her art and life.6

There are many more wartime paintings by incarcerated Japanese Americans that merit careful study, for they offer important pictures by those who lived through a historic trauma as well as varied insights into how these artists grappled with such existential crises and affirmed their place in the world through art. Such wartime works, as seen in The Life and Art of Tokio Ueyama, point to the flourishing prewar and postwar careers that some of these artists had in diverse communities across the US. It demonstrates the vital work of recuperating the extensive artistic output of the pre-WWII generations of American artists of Japanese descent, shifting the almost-exclusive spotlight on Japanese American incarceration toward examining the artists’ full oeuvres and allowing for a more inclusive and accurate history of twentieth-century American art.

-

I must express my gratitude for the generosity of the Ueyama estate—Grace Keiko Nozaki and Irene Tsukada-Simonian, the artist’s nieces, in particular—for allowing me access to the artworks and archives in their private collections since 2015. Few art museums in the United States have Ueyama’s works, with the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles being the exception due to donations from the Ueyama estate. My acknowledgments go to Kristen Hayashi, Director of Collections Management & Access and Curator, and her team for facilitating in-person examinations. ↩︎

-

I am grateful to Noriko Okada’s translation of Ueyama’s diaries that sheds light on the artist’s life in this prewar period. Her translation is included in the Ueyama estate’s donation of the artist’s papers to the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. See “Diary Excerpts Translated into English, 2023,” Tokio Ueyama papers, 1908–circa 1954, bulk 1914–1945, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/tokio-ueyama-papers-22289/series-1/box-1-folder-9. ↩︎

-

Ueyama participated in the 1922 exhibition that Obata and his good friend Matsusaburo George Hibi organized through the East West Art Society, a diverse art collective they cofounded in San Francisco in 1921. See the timeline in this publication. ↩︎

-

See ShiPu Wang, “Archiving for Reckoning: Chiura Obata’s Wartime Work,” Archives of American Art Journal 59.2 (2020): 46–65; and ShiPu Wang, ed., Chiura Obata: An American Modern (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2018). ↩︎

-

Floating Clouds, along with Hibi’s Autumn (c. 1967), Peace (1948), and Matsusaburo George Hibi’s Coyotes Came Out of the Desert (1945), became the first paintings by the Hibis to enter the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2022. ↩︎

-

After Topaz closed in 1945, the Hibis moved to New York City to start a new life, but Matsusaburo died of cancer in 1947, barely two years into their regained freedom. Widowed with two young children, Hisako worked in a garment factory, among other jobs, to support her family. She was able to resume her art career more fully after relocating back to San Francisco in 1954. For Hibi’s art and life, see her memoir, edited by her daughter, Ibuki Hibi Lee, Peaceful Painter: Memoirs of an Issei Woman Artist (Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books, 2004); the children’s book by her granddaughter, Amy Lee-Tai, A Place Where Sunflowers Grow, illustrated by Felicia Hoshino (San Francisco: California Children’s Book Press, 2006); and Cécile Whiting’s “Depicting Place and Displacement,” and Patricia Wakida’s “The Remarkable and Resilient Lives of Hisako Hibi and Miné Okubo,” in Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo, edited by ShiPu Wang (Los Angeles and Berkeley: Japanese American National Museum in association with the University of California Press, 2023). ↩︎